The Church of England is a complex animal because it does not share the possibility for consensus more easily arrived at in the Episcopal Church(TEC). TEC has its voices of minority, yet it draws from a narrower and more homogenous range within the wider social spectrum than does the Church of England, which often strikes us from this side of the pond to be bedeviled by the breadth of its constituency and therefore, the strength of different voices competing with that of the predominant voice of progressive liberalism. Here you can see in the Archbishop’s opening address to the General Synod his attempt to address the complexities of difference within his audience while at the same time sounding an unequivocal call to move beyond the confines of our limited imaginings to embrace the winds of change the Spirit is breathing into and through the Church.

Mark+

Pressmail from St Matthew’s Westminster

View this email in your browser

Archbishop’s call for church revolution

Justin Welby, addressing General Synod in York, 5th July 2013

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby

Before I begin I would like to thank all the staff at Lambeth and around the NCIs, and at Bishopthorpe and the Anglican Communion Office, who have been so effective and kind in dealing with the frightening and unsettling impact of a new Archbishop. Transitions are always very complex, and taking on a new Archbishop is as demanding as it gets. But there’s invariably been a warm welcome and extremely hard work, for which I am extremely grateful. Chief amongst those who have led the way through the process is Chris Smith, the Chief of Staff at Lambeth. After more than ten years of faithful service, working night and day and every weekend – he’s the biggest menace to my capacity to have a quiet evening in on a Saturday night because I get an email from him – after more than ten years of never stopping he is moving on to other things later this year. His contribution has been largely behind the scenes, but he has served the Church of England and the Anglican Communion – not only for a long time but with huge effect – and our debt to him is more than we can imagine. So on your behalf I would like to thank him.

As you know too from public announcements, Bishop Nigel Stock, Bishop of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich, has with great generosity and considerable sacrifice, I’d imagine, agreed to become the Bishop at Lambeth, in a new configuration for the role, working alongside the new Chief of Staff. I could not be more grateful to have such a wise and experienced person, who will enable my many weaknesses to be compensated for more than adequately.

One of the things about this job is you tend to carry a lot of baggage – physical, metaphorical; probably more than I know. We arrived yesterday, the car having broken down en route – there’s a nasty metaphor there. But we did arrive – and we found ourselves with a ton of baggage to carry from one end of what seemed to be a much bigger campus than last year, to the other. And it reminded me – as I was staggering along with what seemed to be enough robes to rival Wippell’s – that we come to this session of Synod with a certain amount of baggage; and it’s good to find ways of getting rid of it. A friend of ours – of my wife and mine, from our days when we lived in Paris – worked for many years for an American company but living in Paris. We went to stay with them about six of seven years ago – he’s now ordained; there’s no connection – and he was still laughing about an experience at Kennedy airport the day before. It was a February and the weather in New York had been very bad, and he’d arrived and everyone was in a grump and the flights were late. And when he got one from the front of the check-in, the person in front of him was incredibly rude to the poor check-in operator. And John, our friend, is always gracious and polite, and when he got to the front he said, ‘I’m embarrassed to be a passenger when people treat you like that. I don’t know how you were so patient.’ And she said, ‘Well, sir. I shouldn’t really tell you this. There’s sort of bad news and good news. The bad news is he’s sitting next to you on the flight to New York. But the good news is I’ve sent his luggage to Tokyo.’

There are a number of obvious applications to that, one of which is we could do with some people like that at the beginning of a Synod session – for the baggage to go somewhere else.

You don’t want a lot of baggage in a revolution. And we live in a time of revolutions. And the trouble with revolutions is once they start no-one knows where they will go. Of the most serious type, the physical type, the practical type… Bishop Angaelos, Head of the Coptic Church in the UK, whom I met in Egypt last week, and who is sitting with us today, knows exactly about revolutions. While we were in Egypt, we heard much talk of what would happen this week – and we’ve seen. And the grace and leadership of Christians in that country is something to behold.

But we live also in a time of many revolutions in this country. And as the Synod meets today, we are custodians of the gospel that transforms individuals, nations and societies. We are called by God to respond radically and imaginatively to new contexts – contexts that are set up by revolutions. I want to thank you, and to say what a privilege it is to share with you, in the ministry of shouldering the heavy burden of facing these changing contexts, and grappling with them in this Synod, now and over the years to come, and to thank you for your commitment in your work here you show to Jesus Christ and to His church. It is genuinely a privilege to be among you.

The revolutions are huge. The economic context and position of our country has changed, dramatically. With all parties committed to austerity for the foreseeable future, we have to recognise that the profound challenges of social need, food banks, credit injustice, gross differentiation of income – even in many areas of opportunity – pressure on all forms of state provision and spending: all these are here to stay. In and through the church we have the call and potentially the means to be the answer that God provides. As Pope Francis recalled so memorably, we are to be a poor church for the poor, however and wherever poverty is seen, materially or spiritually. That is a revolution. Being a poor church for the poor means both provision and also prophetic challenge in a country that is still able and has the resources to reduce inequality – especially inequality of opportunity and life expectancy. If you travel north from parts of Liverpool to Southport, you gain almost a year in life expectancy for every mile you travel. We are debating these questions in this Synod. But prophetic challenge needs reality as its foundation, or it is mere wishful thinking; and it needs provision as its companion, or it is merely shifting responsibility.

The social context is changing radically. There is a revolution. It may be, it was, that 59% of the population called themselves Christian at the last census, with 25% saying they had no faith. But the YouGov poll a couple of weeks back was the reverse, almost exactly, for those under 25. If we are not shaken by that, we are not listening.

The cultural and political ground is changing. There is a revolution. Anyone who listened, as I did, to much of the Same Sex Marriage Bill Second Reading Debate in the House of Lords could not fail to be struck by the overwhelming change of cultural hinterland. Predictable attitudes were no longer there. The opposition to the Bill, which included me and many other bishops, was utterly overwhelmed, with amongst the largest attendance in the House and participation in the debate, and majority, since 1945. There was noticeable hostility to the view of the churches. I am not proposing new policy, but what I felt then and feel now is that some of what was said by those supporting the bill was uncomfortably close to the bone. Lord Alli said that 97% of gay teenagers in this country report homophobic bullying. In the USA suicide as a result of such bullying is the principle cause of death of gay adolescents. One cannot sit and listen to that sort of reality without being appalled. We may or may not like it, but we must accept that there is a revolution in the area of sexuality, and we have not fully heard it.

The majority of the population rightly detests homophobic behaviour or anything that looks like it. And sometimes they look at us and see what they don’t like. I don’t like saying that. I’ve resisted that thought. But in that debate I heard it, and I could not walk away from it. We all know that it is utterly horrifying. to hear, as we did this week, of gay people executed in Iran for being gay, or equivalents elsewhere. With nearly a million children educated in our schools we not only must demonstrate a profound commitment to stamp out such stereotyping and bullying; but we must also take action. We are therefore developing a programme for use in our schools, taking the best advice we can find anywhere, that specifically targets such bullying. More than that, we need also to ensure that what we do and say in this Synod, as we debate these issues, demonstrates above all the lavish love of God to all of us, who are all without exception sinners. Again this requires radical and prophetic words which lavish gracious truth.

The three Quinquennial Goals of growing the church, contributing to the common good and reimagining ministry, are utterly suited to a time of revolution. They express confidence in the gospel. They force us to look afresh at all our structures, to reimagine ministry, whether it be the ministry of General Synod, or the parish church, or a great cathedral, or anything between all of those three. For that reimagination to be more than surface deep, we need a renewal of prayer and the Religious Life. That is the most essential emphasis in what I am hoping to do in my time in this role. And if you forget everything else I say, which you may well do – probably will do – please remember that. There has never been a renewal of church life in western Christianity without a renewal of prayer and Religious Communities, in some form or another, often different. It has been said that we can only imagine what is already in our minds as a possibility; and it is in prayer, individually and

together, that God puts into our minds new possibilities of what the Church can be.

The Quinquennial Goals challenge our natural tendency to be inward looking, calling on us to serve the common good. That covers many areas, and between us all, not singly, we are able to face the challenge. May Synod rise to that. But the second of my personal emphases, within that goal, is reconciliation, within the church but most of all fulfilling our particular Anglican charism to be reconcilers in the world, in our communities, in families, even, dare I say it, amongst ourselves. Even if we do sometimes conduct our arguments at high volume and in public, to be reconcilers means enabling diversity to be lived out in love, resisting hatred of the other, demonisation of our opponents.

The common good goes much further than that. Our unique presence across the country enables us to speak with authority both in parliament and here, and in every church and cathedral and synod and gathering place across the country. Our extraordinary presence across the world as Anglicans enables us to speak with intelligence from around the world. As Anglicans we are called to reconcile incredible differences of culture in over 150 countries. What an extraordinary heritage we have under God. So we seek to be renewed here and across the Communion, and to find the reconciling presence of God. This Synod meets in an era of revolution, but we have together the means and the courage to seize the opportunities that revolution brings.

The Quinquennial goals aim at spiritual and numerical growth in the church. That includes evangelism, the third of my emphases. The lead has been set by the Archbishop of York. Here again we need new imagination in evangelism through prayer, and a fierce determination not to let evangelism be squeezed off our agendas. At times I feel it’s rather like me when I have to write a difficult letter, or make an awkward phone call: even things like ironing my socks become more attractive. We treat evangelism too often in the same way. We will talk about anything, especially miscellaneous provisions measures after lunch on Sunday; and we struggle to fit in the call to be the good news in our times through Jesus Christ. The gospel of Jesus Christ is indeed THE good news for our times. God is always good news; we are the ones who make ourselves irrelevant when we are not good news. And when we are good news, God’s people see growing churches.

Attitudes to hierarchy and authority have changed, and continue to change; there’s nothing new in that. And the more they do, the more we are perceived, often wrongly – but genuinely – to say one thing, about grace, community and inclusion, and do another.

And yet with all these revolutions, which raise such huge challenges to us in our lives as the Church, we see clearly that God is working a wonderful and marvelous revolution through the Church in the wind of the Spirit, blowing through our structures and ideas and imagination.There is a new energy in ecumenism, not least shown by Pope Francis. There is a hunger for visible unity. Many churches across England are growing in depth and numbers. People are looking for answers in a time of hardship and when we show holy hospitality and the outflow of grace, we are full of people seeking us. There is every cause for hope. This Synod had a shock, depending on your view, good or bad, last November; but there is here assembled, in weakness or confidence, in all sorts of fear and lack of trust, people with the faith and wisdom who in grace will seek the way to the greater glory of God.

In some things we change course and recognise the new context. Revolutions change culture. In others we stand firm because truth is not set by culture, nor morals by fashion. But let us be clear, pretending that nothing has changed is absurd and impossible. In times of revolution we too in the church, in the Church of England, must have a revolution which enables us to live for the greater glory of God in the freedom which is the gift of Christ. We need not fear. The eternal God is our refuge and underneath are the everlasting arms.

There have been many times where the Church of England felt that change was in the air or this was a moment of crisis. Because we are not an organisation, let alone a business, or even an institution, but in reality the people of God gathered by the Holy Spirit to walk together in a way that leads to the greater glory of God, there are bound to be many crises and turning points.

So let us not imagine for one moment that because we are in revolutionary times what we are going through currently is either more dangerous, more difficult or more complicated than anything faced by the generations before us. We are in the hands of God; the eternal God is our refuge and underneath are the everlasting arms. We need not worry, but we must give all that we have and we are, for the uniquely great cause of the service of Jesus Christ.

So how we journey here is essential, and that is why during these next few days, certain things are being reimagined: not least what we do tomorrow. What is clear to all of us is that there exists, as we gather – and let’s be honest about it – a very significant absence of trust between different groups; and, it must be said – and the evidence of this is clear, though sad – an absence of trust towards the Bishops collectively.

One thing I am sure of is that trust is rebuilt and reconciliation happens when whatever we say, we do. For example, if, while doing what we believe is right for the full inclusion of women in the life of the church, we say that all are welcome whatever their views on that, all must be welcome in deed as well as in word. If we don’t mean it, please let us not say it. On the one hand there are horrendous accounts from women priests whose very humanity has sometimes seemed to be challenged. On the other side I recently heard a well-attested account of a meeting between a Diocesan Director of Ordinands and a candidate, who was told that if the DDO had known of the candidate’s views against the ordination of women earlier in the process he would never have been allowed to get as far as he did.

Both attitudes contradict the stated policy of the Church of England, of what we say, and are completely unacceptable. If the General Synod, if we decide, that we are not to be hospitable to some diversity of views, we need to say so bluntly and not mislead. If we say we will ordain women as priests and Bishops we must do so in exactly the same way as we ordain men. If we say that all are welcome even when they disagree, they must be welcome in spirit, in deed, as well as in word.

Lack of integrity and transparency poisons any hope of rebuilding trust, and rebuilding trust in the best of circumstances is going to be the work of years and even decades. There are no magic bullets.

So how we travel, and our capacity to differ without hating each other and to debate without dividing from each other, is crucial to the progress we make.

Integrity and transparency depend utterly on a corporate integrity and transparency before God, above all in our prayer and liturgy. I sometimes wonder if one of the drivers of our lack of trust is that we have lost from our experience and our expectation two of the great moods of liturgy: of lament and of celebration. The ability truly to lament, to rage at circumstances, at loss, at decline, at injustice, at our own sin or the problems we face, is one that enables us to find afresh the mercy and grace of God. Lament is a liturgical mood that builds our capacity to trust God in the face of change, and then we trust each other. Encountering the face of Jesus Christ in pain, grief or anger transforms us.

Equally the capacity to celebrate, to lift our hearts and voices in true and passionate praise and thanksgiving because the presence of God is known among, restores our perspective. Not only does it renew our faith and strengthen weary limbs in the long journey we are undertaking, but also the act of celebrating that which we share together cuts across our great barriers and difficulties. We celebrate because who can not be overwhelmed by the love of God?

Take for example the two Anglican Dioceses I saw a week ago in the Middle East, in Jerusalem and in Egypt. In the midst of terrible and confused situations, with unspeakable human suffering, tension and fear, they shine with brilliant light. And they are part of us. In each of them there is a profound commitment to the common good of the populations in which they live as a minority – populations of whatever faith and ethnicity. In each of them there are more schools, hospitals and clinics than there are churches. In each of them the Bishops have established confident and effective relationships with other churches, with Muslim leaders and with governments that enable them to speak frankly and truly and with great courage. And we need to remember that as what they do there affects us, lifts our hearts, shows us the grace and glory and power of God, even more so what we do here affects them and every other church in the Anglican Communion. We have great responsibilities.

We should do no less, be no less effective, no less bold than our brothers and sisters in Christ in those Dioceses; in Nigeria, in Pakistan, in places of persecution and suffering, of revolution, change and disruption. The eternal God is our refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms.

Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your people and kindle in them the fire of your love. AMEN.

© Justin Welby 2013

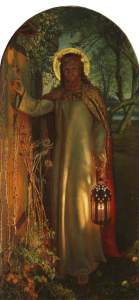

a lamp, knocking at a door overgrown with ivy and brambles. He clearly seeks entry, yet on closer inspection the door has no handle. The implication is that it can only be opened from the inside. What is depicted here is the door of the heart. Hunt captures what it means to knock and the door will be opened. Paradoxically, it is Jesus who is doing the knocking, and it is we who have the power to open or not.

a lamp, knocking at a door overgrown with ivy and brambles. He clearly seeks entry, yet on closer inspection the door has no handle. The implication is that it can only be opened from the inside. What is depicted here is the door of the heart. Hunt captures what it means to knock and the door will be opened. Paradoxically, it is Jesus who is doing the knocking, and it is we who have the power to open or not.