Lauren Belfer’s novel And After the Fire is a story that plays with time. In this instance, the interplay of past and present superimpose upon each other. Traced through events in 18th and 19th century Berlin, Belfer chronicles the fate of a previously unknown Bach Cantata from the chaos of 1945 Weimar to present day New York, Her narrative moves seamlessly from the present back into various periods of the past before reemerging again into the present time.

interplay of past and present superimpose upon each other. Traced through events in 18th and 19th century Berlin, Belfer chronicles the fate of a previously unknown Bach Cantata from the chaos of 1945 Weimar to present day New York, Her narrative moves seamlessly from the present back into various periods of the past before reemerging again into the present time.

I don’t want to spoil the story for you so all I can say is that Belfer not only plays with the interweaving of past with the present but explores the tension between preservation and suppression, between making known and keeping secret.

As they were coming down the mountain Jesus ordered them, “tell no one about the vision until after the Son of Man has been raised from the dead”.

+++

Writing about the Canadian Charles Taylor, to my mind one of the towering figures in contemporary philosophy, Joshua Rothman in his recent op-ed in the New York Times wrote that Taylor:

has explored the secret histories of our individual, religious, and political ideals, and mapped the inner tensions that cause those ideals to blossom or to break apart.

Taylor’s massive opus A Secular Age, which one summer I dedicated myself to working through, explores the historical, religious, and political developments that have led to our arrival in the current secular age. He contrasts how in 1500 it was impossible not to believe in God with the impossibility for many today of holding such a belief, exploring how the culture of the West has moved from one position to the other.

Taylor’s massive opus A Secular Age, which one summer I dedicated myself to working through, explores the historical, religious, and political developments that have led to our arrival in the current secular age. He contrasts how in 1500 it was impossible not to believe in God with the impossibility for many today of holding such a belief, exploring how the culture of the West has moved from one position to the other.

In the long 400-year emergence of our current secular Western mindset, Taylor notes the gradual transition from what he terms the age of enchantment to the age of disenchantment, the term he uses to refer to our current predicament.

+++

The Biblical narratives are the product of enchantment mindset. To the enchanted imagination, God is most frighteningly present in the physical structures of the material world. Divine power not only inhabits objects and places, it makes itself felt through the relational spaces that separate one person from another. It even penetrates our inner worlds of intention as we human being struggle in the tensions between good and evil, between God and self.

The enchanted mindset understands God’s dwellings in spatial terms of up and down, in and out. An expression of the spatial nature of God’s presence in the world is the idea that God inhabits sacred mountaintops. Human encounter with God requires a laborious journey up to the mountaintop where God dwells and where the encounter between divine and human takes place.

On the mountaintop, God conceals Godself in thick cloud while simultaneously self-revealing in blinding light. On the mountaintop Peter, James, and John experience an epiphany of the divine Christ, after which they must negotiate the even more perilous path down the mountain carrying the experience. They must carry the remembrance of what they have seen and yet, at the same time practice a kind of forgetting.

On the mountaintop, God conceals Godself in thick cloud while simultaneously self-revealing in blinding light. On the mountaintop Peter, James, and John experience an epiphany of the divine Christ, after which they must negotiate the even more perilous path down the mountain carrying the experience. They must carry the remembrance of what they have seen and yet, at the same time practice a kind of forgetting.

Many have been perplexed why Jesus so insistently binds his companions to the silence of secrecy? I am reminded of Belfer’s novelistic exploration of the tension between preservation and suppression, between making known and keeping secret.

The easiest explanation for Jesus binding his companions to secrecy is that the time is not yet right. Events on the mount of the Transfiguration are only at a midpoint in a longer process towards the dénouement of his ministry.

As they were coming down the mountain Jesus ordered them, “tell no one about the vision until after the Son of Man has been raised from the dead”.

+++

The Transfiguration story is a halfway point for Matthew and the other gospel writers. It marks the transition when Jesus leaves preaching and teaching in the Galilean countryside and turns his face towards to Jerusalem.

The event on the Mountain of Transfiguration is also for us a halfway point between Jesus’ birth and death. The Transfiguration is a momentary glimpse through the space-time continuum as it were into the unity Jesus enjoys with God. Yet, at this stage of the journey, it must be preserved in secrecy, for the journey is only halfway through.The danger for us is to play with time in an unhelpful way, to impose the future onto the present before we are ready for it.

Jesus’ point to Peter, James, and John is that they are not yet ready to bear the full realization of what they have witnessed on the holy mountain. The danger for them is that the transfiguration becomes a high point, a peak experience that they hanker endlessly to return to; a state for which they yearn rather than a stage through which they emerge.

If I had revealed the plot and ending of Belfer’s story I would have spoilt your experience in reading it. Yet, when it comes to the gospel we know the plot and how it ends. This distances us from the day to day experience of living through the story and its power to interact with us as it unfolds. We miss the point that this story must be lived through in temporal time, one day at a time. Because, at the level of everyday experience, like Peter, James, and John, we find that we too are not yet ready for the full implications of its ending.

The Transfiguration bookends the Christmas-Epiphany season. From here on we move into a different section of the spiritual journey. The landscape becomes rocky and desert-like as we journey down the mountain into the season of Lent.

Our upcoming encounter with the themes of Lent will show us just how ill prepared we are to receive the fullest insights of the Transfiguration. Lent offers the opportunity to open more profoundly to the transformation process that will prepare us for the last great epiphany of Jesus’ earthly life – his death and resurrection.

+++

If God was powerfully present within the material structures of the enchanted age, God has been locked outside of the structures of our disenchanted age. For us, the material universe is an experience of being alone.

Yet within our disenchanted age, the Church’s calendar continues to move us along a journey taking us from Jesus birth to his death and into new life. The Bible despite being the product of enchanted imagination still offers us the only narratives which have the power to shape and fulfill our otherwise disenchanted lives.

Transfiguration is not a state we yearn for, but a stage we emerge through as we journey onwards into the processes of personal and community transformation. Yet for that to happen we have to possess the courage to place God and the center of our living and loving. Can we? Will we? These questions will go to the heart of our study over the next six weeks.

are entering to possess. But if your heart turns away and you do not hear… I declare to you today that you shall perish; you shall not live long in the land that you are crossing the Jordan to enter and possess.

are entering to possess. But if your heart turns away and you do not hear… I declare to you today that you shall perish; you shall not live long in the land that you are crossing the Jordan to enter and possess.

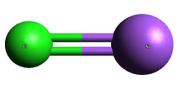

Salt can’t lose its salinity unless the chemical bond between sodium and chlorine is broken. As one of the most stable of compounds, only an electric charge is able to loosen the NaCl molecule. Thus when salt is dissolved in water it enjoys a greater volume as it is released from crystal form, but it remains essentially salt in all its savory-ness.

Salt can’t lose its salinity unless the chemical bond between sodium and chlorine is broken. As one of the most stable of compounds, only an electric charge is able to loosen the NaCl molecule. Thus when salt is dissolved in water it enjoys a greater volume as it is released from crystal form, but it remains essentially salt in all its savory-ness.