It’s Friday morning and after a hectic week I finally turn my thoughts to today’s readings for the second Sunday in Lent. Bereft of helpful insights – I scratch my heard as I read that Jesus tells us – his modern-day disciples – to deny ourselves, take up our cross, and follow him – that the cost of saving our lives lies in our willingness to risk losing them?

Nightly images numb me further into acquiescence and resignation as I watch in real time as the civilian population of Gaza is bombed into a stone age wasteland of wretchedness beyond belief.

News from Oklahoma of a young trans person’s death as a result of a bathroom incident between fellow students in a school – further evidences the unleashing of politically sanctioned persecution of trans and nonbinary persons in large parts of this country.

In States governed by legislatures no longer committed to the basic principles of representative democracy – where power is maintained through gerrymandered electorates – legislatures pursue their anti-liberal agendas – and the courts continue to hand down insane rulings that impose increasingly cruel and unusual punishments that further restrict the basic civic freedoms to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness enshrined in the Constitution. We’ve reached the ludicrous situation where the courts defend freedom of speech protections that allow the right to incite hatred but strictly policing student hairstyles.

I hear a voice in my head cautioning me to stop it! Stop what? Well stop funneling down the rabbit hole of rage and despair. Forty years of experience reminds me that this is no good way to begin a sermon reflection.

At the root of my despair is my rage that the world is not fair, that wrongs seem seldom righted. Everywhere I look the appearance of things leads me to conclude that despite my frequent protests to the contrary, might is often right and wealth is the primary influence on power. It’s into this slough of despond I hear Jesus speaking to Simon Peter: Get thee behind me Satan. The words of the King James Authorized Version – a translation I hardly ever read – remain indelibly imprinted on my mind as is probably true for most English-speaking Christians.

To fully appreciate the searing impact of Mark’s account of the encounter between Jesus and Simon Peter we need to go back to verse 27 of chapter 8 where Mark reports Jesus on his way to Caesarea Philippi. Along the way he asks his disciples what are people were saying about him? Reporting the general gossip – the disciples tell him: Well Rabbi, some say this, and some say that. To which Jesus asks: But you – who do you say I am? His question provokes Simon Peter to declare: We know who you are, you are the Messiah! But giving the correct answer doesn’t necessarily mean understanding what that answer means.

Today’s text picks up at verse 31 with: Then he began to teach them —. But what Jesus teaches them is not what they want to hear. Simon Peter – with his Jewish conditioned misunderstanding of messiahship confronts Jesus. Taking him aside he rebukes Jesus with what I imagine probably went like this:

What on earth are you talking about, Jesus. What nonsense are you spouting about suffering and death. You are the Messiah – the great king sent by God to get us out of this mess of Roman occupation and restore us to our status of a chosen nation. So, let’s hear no more of this defeatist nonsense about suffering and death. Can’t you see the undermining effect on our morale when you speak like this?

Jesus fixes Simon with a steely gaze and with a heart stopping authority commands: Get behind me Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.

This is a hard saying. Trapped within our human perspective we look out at the appearance of things – unable to see beyond our limited perceptions to the larger picture. So much of the divine action remains hidden from our view.

Can we with any honesty speak in a community like ours about Jesus’ prediction of suffering and death? Like Simon Peter, suffering and death as the cost of discipleship are not on our agenda – no matter how darkly at times we may view events in the world around us. Unlike Peter we don’t even have the courage to protest the point. We just tune out – preferring to think the choice is ours whether to follow Jesus or not. We may choose to follow Jesus, but always on our own terms – at little cost to ourselves.

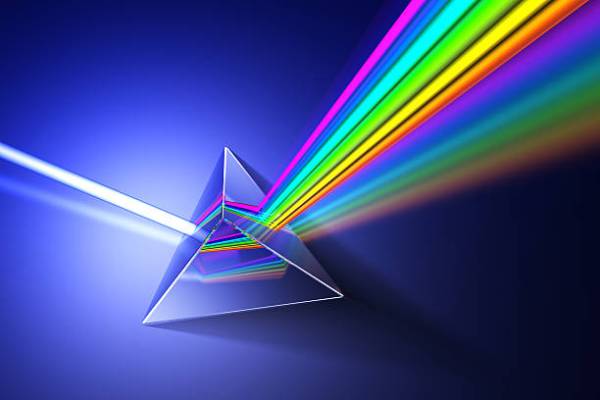

Like Simon Peter and the Disciples we want to filter Jesus’ messiahship through the prism of our own desires and fears – the things of our human priorities.

Prisms. Now here’s an interesting fact. The thing about prisms is that they don’t filter light – they refract it. White light enters as a beam to become refracted into the seven-color constituents of the spectrum. Our desires and fears – our human priorities enter the prism of Jesus’ messiahship as a tight beam of white light and emerge refracted to reveal the divine priorities in a multi-stranded, Kodachrome cone of ever-widening dispersion.

An event of ultimate significance occurred this week – shedding some light on this incident in Mark. I refer to the death in suspicious circumstances of Alexei Navalny -the courageous Russian dissident and now martyr for the democratic cause. Many of us still find it incomprehensible that he chose to return to Russia knowing the fate that awaited him. It seems that in this action, with his mind no longer focused on his own concerns – Navalny understood the cost of discipleship as inseparable from fidelity to the path of discipleship – which for him was the cause of democratic freedoms.

I am not in any way conflating Alexei Navalny with Jesus. I don’t know whether Navalny was a Christian believer or not. My point is – Navalny emulates Jesus in action. They both knew that being faithful to their cause would cost them nothing less than their life. They both wielded the most powerful weapon in the confrontation with evil – that of nonviolent resistance.

Like Pontius Pilate before him, as the representative of empire, Vladimir Putin understands well the necessity of killing the leader of a movement for nonviolent resistance. Like Pilate and countless other brutes of history before him – Putin fails to understand that non-violence is an idea that only strengthened in killing its leading proponents. As with Jesus, the concentrated white light of Alexei Navalny’s life has now been refracted through the prism of his death into a broad Kodachrome spectrum of ever widening hope. But hope comes at a cost and when the cost is paid – hope strengthens.

What will it take for us to discover what the disciples eventually came to understand – that the fruit of discipleship is inseparable from its cost?

The cost of discipleship is paid in the currency of hope’s confrontation with evil. What will discipleship cost us? This is Jesus’ 21st century discipleship question to which the life and death of Alexei Navalny reveals one possible answer.

Discipleship is unlikely to cost us our lives. But it does require our death to self – a death to our self-preoccupation – a dying to our exclusive focus on merely human things that lead us to despair and acquiescence to helplessness.

As we enter upon the journey of another Lent – a season in which we are called to face-down the temptation to acquiesce in the face of the evil that holds such sway in the world around us. Lent is a season when the white light of despair is refracted through the prism of discipleship into the broad color spectrum of faith, courage, and love – to name but three stands in the spectrum of hope. But be under no illusion – the path of discipleship is a costly one – as Navalny’s death confirms. And the encounter between Peter and Jesus in Mark 8 is where for us the journey of discipleship begins. It’s from here we reset our compass needle towards the resurrection.