The parable of the Prodigal Son occurs only in Luke. Among all Jesus’ parables in Luke this one captures the singular tone of Luke’s humanistic presentation of Jesus.

In 2013, in a sermon on this text titled A Punch to the Gut, I drew out the parallels between Luke’s parable of the prodigal and Hogarth’s 18th century series of drawings in A Rake’s Progress – chronicling a young man’s unravelling from fashionable young buck- about-London-town – newly come into his inheritance – to that of a broken man – destitute and driven mad with syphilis he’s incarcerated in the famous Bedlam hospital where along with the other inmates he becomes an object of curiosity for the fashionable of the day who loved to gape at the inmates as if they were animals in a zoo.

A fun fact is that the first hospice for the mad was dedicated in 1267 as the Priory of St Mary of Bethlehem at London’s Moorgate. During the reign of Henry VIII, the priory was dissolved and reestablished by royal charter as the Bethlem Royal Hospital – where I served as chaplain for 18 years. In the 17th century, the name Bedlam – a popular derivation of Bethlem became a synonym for chaos and madness and which today remains in common use.

In 2013 I focused on the destuctive narcissism of the young man as psychologically illustrative of the process Luke describes in his parable of the prodigal son. Then I wrote of the younger son seeing other people and situations as simply an extension of his own wants and desires. He cares little for his father, or brother, nor for the women he consorts with. They are simply the momentary extensions of his own wishes- needs, and to him have no life independent of what and who he needs them to fulfill his desires. At the lowest ebb of his life, is it the emergence of sorrow and repentance that reminds him of his father’s love, or is it his narcissistic expectation that his father will once again meet his needs regardless of his actions? Such a myopic psychological analysis seems a rather indulgent luxury when viewed from preaching demands in these more turbulant times.

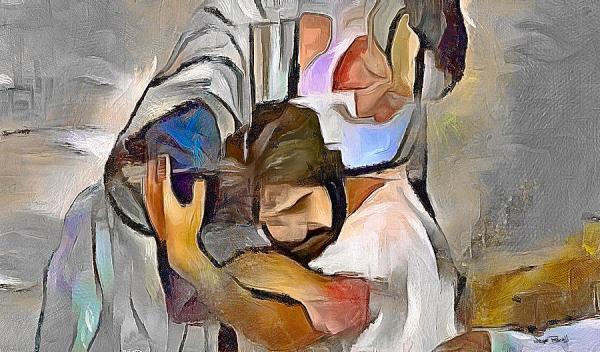

Today I’m more conscious of the parable’s multilayered complexity. It’s a story as much about the elder son as the younger – as much about the father as either of the sons. Taking Luke’s parable as the parable of a loving father – provides a different starting point for my reflection on the text today.

Who among us does not know the experience of a wayward child? If that is too strong an expression at least many of us will know the pain and concern felt when our children begin to chart courses in life very different from the ones we had anticipated for them – making decisions we would have wished they made differently.

Luke sketches out the scene as Jesus leaves the synagogue where he’s been engaged in a long discussion with the Pharisees following the Shabbat service. As he comes out into the street, he’s mobbed by a crowd who had been loitering with intent to waylay the teacher outside the synagogue doors. In describing them as tax collectors and sinners, Luke is drawing our attention to the fact that these are the ritually unclean, those who would not have been allowed through the synagogue’s doors. Unable to listen to Jesus’ debate with the Pharisees inside, they are eager to hear him nevertheless. The Pharisees, following Jesus out into the street begin to grumble behind him about the shameful way Jesus is mixing with the ritually unclean. Clearly aware of their grumbling he begins to tell everyone this parable: There was a man who had two sons —. .

We can’t know with any certainty what ending the crowd outside the synagogue – both the virtuous pharisees and the ritually unclean expected from this parable. But we do know how subsequent interpretations have sought to reduce it to a rather simplistic morality tale about the wages of sin with strong patriarchal themes of judgment about sex with prostitutes, disobedience to fathers, and the wages of sin contrasted with the importance of duty. The younger son, in following his hedonistic desires, comes -predictably – to a sticky end. When hard times overwhelm him, he is forced to humiliate himself by going back home with his tail between his legs to beg his father’s forgiveness. You can hear the tut tutting down 2000 years of interpretation – be this a lesson for all you rebellious sons.

Both moralistic and psychological interpretations of the text focus on the motivation of the younger son, ignoring both the responses of his elder brother and his father. What about the elder son’s reactions to his brother’s return? What about the father’s inexplicable pining for his profligate son’s return? Both challenge the traditional worldview of this parable as a morality tale.

This parable offends against the traditions that emphasize the virtues of obedience and duty to strict fatherly rule and the honoring of the firstborn over the younger. It challenges the virtues of blind filial duty. It skirts over being dutiful and hard working on the family estate seems to have bred in the elder son only a deep sense grievance – an envious resentment of his brother and a disparaging contempt for his father. In confronting his father, he refers to his brother not as my brother but as this son of yours – aptly articulating his anger towards both.

The traditional reading of this story is likewise conflicted on how to picture the father – whose indulgent generosity flies in the face of conventional inheritance custom. His willingness to take back his son – failing to hold him to account for his profligate ways smacks of more than a little moral weakness if not an indulgence dangerous to hierarchical moral order.

Reading this story through the filter of patriarchal relations has been one of the two main ways this parable is favoured by tradition. The other has been to read it through the filter of antisemitism. The father is God. The elder son represents the Jews. and the younger son, the Christians. We can all see where this reading is headed.

But if Jesus were standing in this pulpit, orienting himself to our 21st century mindset he might ask so who do you identify with in this story? This is not simply a question for us as individuals – it has wider social-relation implications. As middle-class folk, dutiful, obedient, hardworking, and schooled in the virtues of delayed gratification, I imagine few of us identify with the headstrong younger son and his deeply narcissistic and self-destructive choices.

Reading the story through the lens of the prodigal son simply confirms our moral judgment of him as selfish and irresponsible – or a psychological interpretation of him as emotionally and psychologically immature. Both comfortably distance us from him and his choices. Reading the story through the lens of the elder son is likely to evoke more sympathy in us. We easily identify with his feelings and reactions – for who among us has not had an experience of being passed over in preference to another. However, it’s when we read this parable through the lens of the father – in other words, hearing the parable through the filter of his feelings and responses that we discover our disapproval of his indulgent, seemingly uncritical and nonjudgmental welcoming of his son’s return. He not only fails to call his son to account but throws caution and financial prudence to the winds – giving completely the wrong signal by appearing to reward bad behavior with a lavish party.

We can’t know how his 1st-century hearers, thronging the road outside the synagogue, expected this story to end. Yet for us today, the parable certainly carries a sting in its tail. We can be clear that Jesus is primarily painting a picture of God as a noncritical and non-judgmental father. God is recklessly generous, failing to discriminate between the worthy and unworthy as recipients of his love. God is a vigilant father whose is by his nature compelled to keep a watchful vigil in the hope of his wayward children’s return. Jesus paints a picture of God as a shockingly indulgent father who treats our return as the occasion for a wild celebration of new life – for his son who was as good as dead and has now come back to life – lost and now found..

The question remains, however, how does this picture of God leave us feeling? We may be happy to imagine ourselves as the recipients of such reckless generosity. But as a model for us to emulate towards anyone who has the power to hurt and disappoint us – we might feel some ambivalence.

Like all of Jesus’ parables, it operates at two levels. In the setting of its telling – the street outside the synagogue – the Pharisees can be depicted as the sincerely religious – men of real integrity and longing to know and love God more. Yet, their ability to be sincere in their spiritual quest is a product of their privileged social and economic status. In debate with Jesus, they are intrigued but remain cautious for being the privileged; they feel that they have much to lose. They want to know what the right path is before they commit to following it. Contrastingly, it’s those whose occupation or lack of one excludes them from among the company of the righteous – who have nothing to lose and who seem open to, and excited by, the invitation implicit in this parable.

We don’t know if the elder son did eventually swallow his hurt pride and join the feast – the parable leaves us with this possibility, for the father’s invitation is open-ended.

Although the parable does not have a clear concluding moral message, it nevertheless has a rub that chafes. The rub is – grace is never free. Oh, it’s offered freely by God and there is no pre-qualification required to receive its invitation. The offer is free, but the acceptance is costly. Identifying with the elder son – what would it cost us to relinquish our resentment and go into the feast? If we can identify with the younger son – what would it cost us to return home, humiliated?

The younger son knows that the grace of the father’s undying love is costly. Both the Pharisees and the tax collectors know that grace is costly. For the Pharisee, it’s costly to give up a presumption of righteousness. For the socially marginalized and religiously excluded, grace comes at the cost of lives of humiliation.

Like the father in this parable, who among us does not know the cost of unconditional, nonjudgmental love? Who among us has not suffered the pain of watching our children chart different life trajectories that either lead to painful and unsuccessful outcomes or hurt us in their rejection of our values and assumptions? We know that, like God’s grace, our love is not free; it exacts its own cost.