Image: Table Talk – Arrington & Associates arringtonassoc.com

We’ve been listening to the voice of the prophet Jeremiah for the last three weeks in our OT readings. So who was he?

Jeremiah was born in the Levite village of Anathoth, located just outside Jerusalem, in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin. Being from a priestly family not connected to the Temple worship in Jerusalem, he was close enough to know the ways of the Temple, but far enough from its center to see its faults. As a young man, God called him. Jeremiah resisted—“I am only a boy, a dresser of sycamores,” he said—but God put words in his mouth and sent him out to speak hard truths: not only to uproot and tear down, but also to build and to plant.

Not unlike our own day, Jeremiah lived in a time of deep turmoil. Leaders were corrupt, religion was shallow, and the nation was on the brink of collapse. He warned: Babylon was coming, and Jerusalem would fall. No one listened. He was mocked and imprisoned for treason. As the city was about to fall, he was thrown into a dry cistern and left to die.

For the first Christians, Jeremiah evoked their memory of Jesus. Remembered as the weeping prophet, his tears flowing from a deep love, he wept because his people would not listen. And yet he never gave up hope. He even bought a plot of land as a sign that God’s people would one day return and rebuild. He embodied hope. He looked ahead to a new covenant, not written on stone tablets but written upon the human heart.

It is no wonder the early Christians saw Jeremiah as a prototype of Jesus—one who suffered for speaking God’s truth, whose heart broke for his people, and who pointed beyond judgment to God’s steadfast promise of new life.

Jeremiah’s vision still speaks to us today. Faithfulness is not always easy, but it is always rooted in love. Jeremiah shows us that even when old ways collapse, God is planting something new. The question is: will we make that essential leap from the external observance of religion as a series of rules and rituals to the power of internal tranformation. Or as Jeremiah phrases it: will we allow God’s covenant to be written upon our hearts?

In “The Cost of Resistance” and “Religion, Conduit or Smokescreen?“ – my last two sermons, I addressed the importance of resistance, either as non-violence, which allows for confrontation or non-resistance, which rejects confrontation in favor of identification with the oppressed. Both were crucial elements in Jesus’ challenge to religious and political authority. Jesus echoed Jeremiah’s call for a new covenant, not of empty ritual, but of inner transformation – a covenant no longer written in stone and enforced by law, but one written upon the human heart and empowered by love – not sentimental love, but love as the robust expression of mercy at the heart of God’s justice.

In chapter 14, Luke relates a story about Jesus attending a dinner. For Jesus, a dinner is never just a dinner. It’s a metaphor for the world.

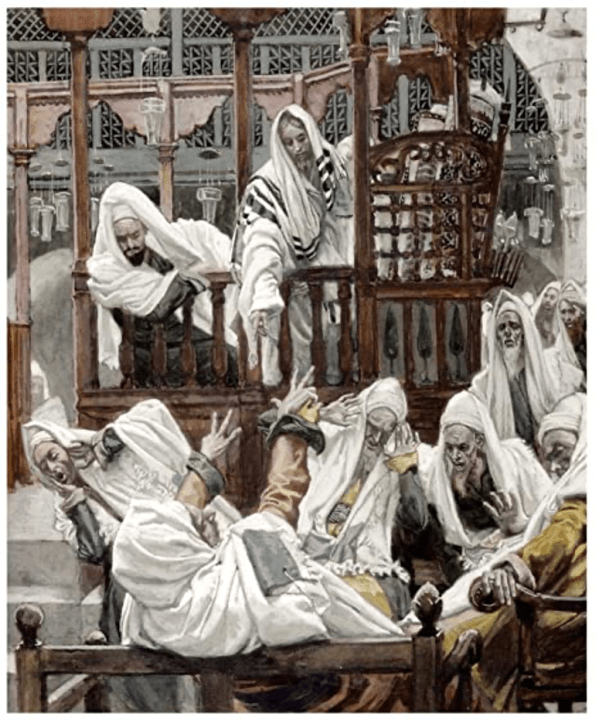

In Luke 14, Jesus is at a Pharisee’s house on the Sabbath. He watches people scramble for the best seats, angling for honor. He sees the host inviting all the right people—friends, relatives, wealthy neighbors—the kind of guests who can return the favor.

And Jesus says: Not so in God’s kingdom.

First, he speaks to the guests: Don’t grab the best seat. Take the lowest place. Because in God’s world, all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.

This isn’t just table manners. This is a whole new way of thinking about status. Honor is not seized. It’s given. It’s gift.

Then he turns to the host: When you give a banquet, don’t invite the people who can pay you back. Invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. Invite the ones who cannot repay.

That’s radical. Not only in the ancient world, but throughout human history, meals have been about reciprocity—keeping the social wheel spinning.

Jesus says: Stop calculating. Stop expecting a return. Throw open the doors.

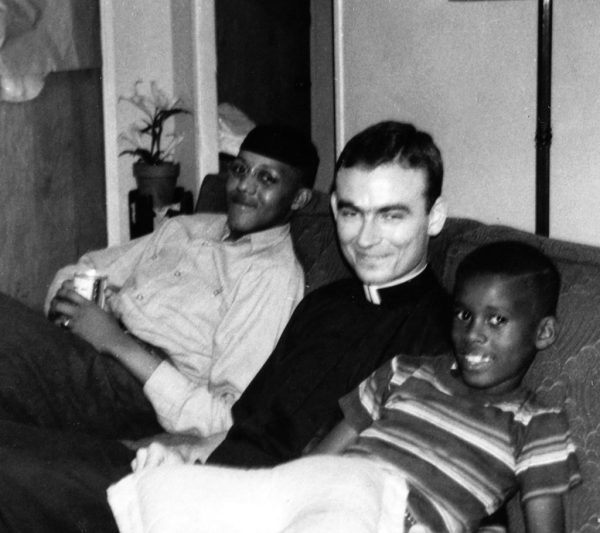

As a young man, I remember one evening at a soup kitchen. I expected to serve from behind the counter. But the priest said, “Sit down and eat with our guests.” I did—and found myself laughing and sharing stories with people who had nothing to give back but themselves. One man even offered me the last piece of bread. That night, I realized the kingdom isn’t charity. It’s communion.

A few months ago, I read about a small church on the southern border. They opened their parish hall to migrant families who had nowhere to sleep. No repayment possible, no guarantee of safety or security. Just beds on the floor, warm food, and open doors. The world might see it as impractical, even dangerous. But I think Jesus would see it as a rehearsal dinner for the kingdom banquet.

And I think too of the early church, where at Christian gatherings, slaves and masters, men and women, rich and poor, Jews and Gentiles sat at the same table. In the empire of Caesar, that was unthinkable. But in the kingdom of God, it was the most natural thing in the world. The table re-ordered society.

The table is just the beginning. Jesus is describing a whole new way of life, and the implications for us can be rather disturbing. In a world obsessed with status, Jesus points us toward humility. In a world built on transactions, he points us toward generosity. In a world that excludes, he points us toward radical welcome.

Our economy thrives on profit and return. But Jesus says: invite those who cannot repay.

Our politics builds walls and charts borders. But Jesus says: the kingdom is not complete until the stranger is welcomed.

Our relationship with creation is marked by exploitation. But Jesus says: take the lower seat, live humbly as a guest at creation’s table. Reduce your carbon footprint by curbing your discretionary spending on things that are not necessary but only desirable. Maybe some of these decisions are now going to be forced on us, if not by virtue then of necessity, as our minds begin to boggle at increased prices, and our fingers are slower to click the Amazon complete purchase button.

Our nations compete for dominance, our corporations scramble for power. But Jesus says: true greatness is found in service, not control.

And here, at this table—the Lord’s table—we taste that world. No reserved seats. No VIP section. All come empty-handed. All are fed by grace.

Luke 14 is not about table etiquette; it’s about God’s dream for the world:

- A world where generosity replaces calculation.

- Where strangers and migrants are honored guests.

- Where creation is cherished.

- Where humility dethrones pride.

- And where grace, not power, is the currency of life.

This is the banquet of God. This is the feast of the kingdom.

Jeremiah’s words ring out across the centuries. Even in times of turmoil, God is still at work—tearing down what cannot last, and planting seeds of hope for what will endure. May we have the courage and the love to live as people of this promise – a covenant written upon our hearts.

I know most of us will be thinking, though few I imagine will say it out loud, that this is all very well and good – a wonderful utopian picture impossible to achieve. How often are we told that the dream of God is not reality. But before we rush with something of a secret sigh of relief to dismiss utopian dreams, let me leave us with this thought. Coming down to the intimacies of our everyday lives, if we share this bread and drink from this cup, might it be possible for this table to begin to reshape all our other tables—our homes, our neighborhoods, even our politics. Is this such an impossible dream?

Amen.