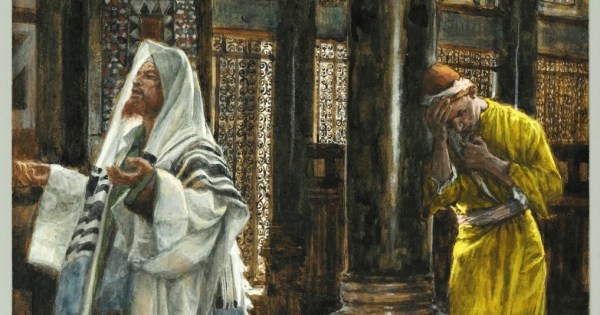

Image: The Pharisee and the Tax Collector, James Tissot, 1886-1894

Any attempt to speak about money in the church runs the risk of provoking a cynical or defensive response. We’ve all heard it before — “the church just wants my money.” But this reaction misses the point.

Money, in the life of faith, is only ever a metaphor for values. When we commit to financially supporting an organization — especially the Church — our hope is not only to contribute value but also to derive a sense of value. Both are essential to living meaningfully with purpose.

One of the great paradoxes at the heart of Christian life is that spiritual renewal is so much more than money, and yet financial generosity is a key expression of our deepening awareness of our need for God. But money and religion often make for a volatile mix.

Putting religion aside for a moment, our attitudes and feelings about money evoke in many of us a deep-seated anxiety — the scarcity–abundance paradox.

I can trace my own anxiety about money back to my parents arguing about it. As the eldest child, I witnessed the early days of their marriage when money was the powerful metaphor for their fears of scarcity as they struggled to build a stable life.

What about you? What are your earliest memories of family conversations around money? Was money, in your home, a metaphor for enoughness or for scarcity?

We internalize — without being conscious of doing so — the anxieties transmitted to us during infancy and childhood. In my case, an expectation of scarcity was implanted in me, even though enoughness — even abundance — has been a much stronger feature of my adult life.

This tension between expectation and experience is exactly where God begins to work.

The Old Testament reading from Joel speaks into this space. After years of drought, famine, and devastation, Joel delivers a word of hope:

The threshing floors shall be full of grain,

the vats shall overflow with wine and oil.

That would have been miracle enough — but Joel goes further:

Then afterward, I will pour out my spirit on all flesh;

your sons and your daughters shall prophesy,

your old men shall dream dreams,

and your young men shall see visions.

God’s promise is not only enough to survive, but enough to dream again.

We often associate “abundance” with endless surplus. That’s why I prefer the word enoughness. Abundance means sustained enoughness — a way of living rooted in trust rather than fear.

Trusting this promise is risky. It requires relinquishing the illusion of being in control — the illusion that we are the authors of our own security. For those of us shaped by scarcity fears, God’s promise of abundance is not easily believed.

So we must ask: Which is more real — our fear of scarcity, or the evidence of our own experience?

Scarcity says: there won’t be enough.

Enoughness says: there is always enough.

Fear blocks generosity. Trust makes generosity possible. When we look honestly at our lives, we discover how often fear has misled us. Most of us live every day with enough — and more than enough. The critical question becomes: Which story do we choose to inhabit?

America may well be the most prosperous society in human history — and yet, paradoxically, we experience the highest levels of scarcity anxiety fueled by the myth of self-sufficiency. In the land of plenty, we too easily condone poverty and inequality, justifying these conditions as the consequences of personal and moral inadequacy.

To abundance understood as enoughness, God calls us to add the practice of justice. Generosity is not just an act of kindness — it is a protest against the myth of scarcity and the injustice that flows from it.

In today’s Gospel, Jesus tells of two men who go up to the Temple to pray: a Pharisee and a tax collector.

The Pharisee believes himself the author of his own salvation. He stands tall, proud of his accomplishments, loudly proclaiming them before God.

We know we are supposed to side with the tax collector, and yet — if we are honest — many of us live more like the Pharisee, designing our lives so we will never need anything from anyone.

But the tax collector — standing apart, unable even to lift his eyes — knows his need of God. In that posture of honest dependence, he discovers a truth the Pharisee cannot: everything — even the good we do — flows from God’s grace, not our control.

The source of all our loves in life flows from God’s love for us. Only when we acknowledge this can we begin to understand our need for God.

Generosity is not a financial transaction — it is a spiritual practice, a way of saying:

I trust in God’s unstinting generosity.

This stewardship season invites us to remember that none of us is an island — our lives are bound together in God’s shared abundance. Through mutual generosity we accomplish far more than any one of us can do alone. Through giving, time, participation, and compassion, we remind each other that abundance is not personal achievement but the fruit of life in community.

Between now and November 24th, I invite each of us to cultivate practices of generosity — for our spiritual, emotional, and societal flourishing. Generosity is not simply about sustaining a budget — it is about extending ourselves to realize God’s promise of enoughness.

Every act of generosity participates in God’s dream for justice.

And so we return to Joel’s vision:

I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh;

our sons and our daughters shall prophesy;

our old men shall dream dreams;

our young men shall see visions.

So this Stewardship season, let’s dream of unleashing our generosity to achieve yet-to-be-imagined possibilities.