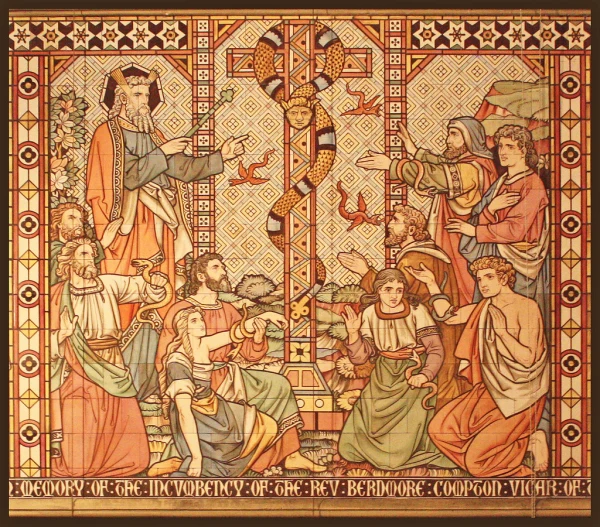

Picture: Chapel of the Ascension, Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, Norfolk, England

There is a rather ugly 1960s chapel at the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham – deep in the rural countryside of the county of Norfolk dedicated to the Ascension of our Lord. On entering the Chapel of the Ascension, one is greeted with a surreal experience. For in the center of the low ceiling is a gilded cloud ring plaster rosette from the center of which hang two bare feet – suspended in the air. Ostensibly belonging to Jesus with the rest of his body having already burst through the ceiling.

The celebration of the Ascension always occurs on a Thursday – the 40th day after the resurrection. Because Episcopalians rarely venture to church except on Sundays – the current custom is to celebrate the Ascension of the Lord on the Sunday following – which in 2024 also incongruously happens to be Mother’s Day.

Incidentally, I heard a funny quip recently referring to the Southern Baptist church calendar which comprises only four commemorations: Christmas, Easter, the 4th of July, and Mother’s Day. It goes without saying that while we shouldn’t pass up any opportunity to celebrate the importance of mothers and mothering in our lives, in the Episcopal Church, Mother’s Day is not part of the liturgical calendar.

Constructing stories and weaving narratives are the way we make sense of our experience of the world. The perennial question concerns the relationship between story and material experience – in other words, does weaving narratives – telling stories interpret and explain our material experience, or does the power of narrative – in the words of the French deconstructionist philosopher Michel Foucault – construct our experience – as in language creating the objects and meaning of which it speaks.

This tension surrounding the function and power of language is especially pertinent when it comes to religious-spiritual stories. Narrative Theology asserts that spiritual meaning lies not in the literal veracity of the events depicted – did they happen or not – but in the function of story by itself to construct and convey purposeful meaning across time. The question is not whether or not Bible stories depict actual happenings – but how they construct meaning and purpose that can be trusted to shape our living?

Spiritual stories recycle human imaginative memory. Clearly, Luke’s graphic account of Jesus’ Ascension borrows extensively from Elijah’s ascension recorded in the 2nd book of Kings. In like manner – as the mantle of Elijah fell upon the shoulders of Elisha – giving him a double portion of his master’s spirit, the double portion of Jesus’ Spirit clothes the disciples. The resonance is unmistakable.

In Luke’s chronology of events from Calvary to Pentecost, his story of the Ascension of Jesus forms a transition point bringing the earthly ministry of Jesus to a close to empower his followers with his spirit to become a community equipped to continue his work. The question underlying the Ascension event is not how, when, or if it happened, but what light does it shed on the question of what’s next?

The question of what’s next throws into sharp focus the choices to be made, the actions to be taken, and the directions to be followed.

In her sermon last week, Linda+ noted that love is not just about how we are to feel. It is about who we are called to be. Rather than asking: What does it mean to believe in God’s love – she posed the more significant question do we trust God’s love, do we surrender to it, will we let love transform us?

So here’s a question. How can we trust the meaning inherent in the story of the Ascension of Jesus even though most of us believe it as an event to be simply a construction of imagination?

One response is to substitute the traditional spatial metaphor of up and down for heaven and earth with a metaphor more suited to contemporary imagination – that of heaven and earth as side by side. The Ascension becomes the conduit connecting parallel dimensions. Through this conduit a two-way traffic flows between what we might call our space and God space.

The image of the Ascension of Jesus as a conduit for two-way traffic communicates two important insights. In his return to the God space, Jesus does not jettison his humanity like a suit of worn-out clothes – but carries the fullness of his humanity – perfected through suffering -to be received by God into the divine community. The words of the first collect for the Ascension capture this: that as we believe your only begotten Son our Lord Jesus Christ to have ascended into heaven, so we may also in heart and mind there ascend, and with him continually dwell. The we here is not us individually, but the entirety of our humanity which now constitutes an element within the divine nature.

In receiving the fullness of Jesus humanity into the divine nature, God releases the divine spirit of Jesus to make the return journey back into our space. This image is captured in the words of the second collect for the Ascension: our Savior Jesus Christ ascended far above all heavens that he might fill all things and to abide in his church until the end of time. The Ascension is the point where we, Christ’s mystical body on earth are prepared to become empowered to continue the work Jesus began.

The Ascended Christ bearing our perfected humanity is received into the heart of God – so that – as the book of Revelation poetically phrases it – the home of God now dwells among mortals. Now we come to the most extraordinary assertion of Christian faith – that from henceforth to be most fully human is to be most like God.

The Ascension of Jesus opens us to contemplate our participation in the what’s next in God’s work of renewing the creation -throwing into sharp focus the choices to be made, the actions to be taken, and the directions to be followed – when we tire of gazing heavenwards – that is.