On the fourth Sunday after Easter – traditionally referred to as Good Shepherd Sunday – it is customary for the preacher to explore the protective and nurturing metaphor of shepherding. As many of you know I’ve explored in previous years how the metaphor of the shepherd and the dynamics of shepherding offer a sharp contrast between modern and 1st-century methods of sheep farming. Good Shepherd Sunday also has a habit of falling on Mother’s Day and I’m somewhat relieved that this year we’re still two weeks ahead of that sermon challenge.

Coming from a country such as New Zealand – a nation of five million humans and over 40 million sheep – the life of sheep and that of the shepherds who manage them is somewhat familiar. In previous sermons on Good Shepherd Sunday, I’ve spoken of my nephew Hamish, who farms a hill country station – sheep farms are known as stations in the rugged hill country of NZ’s South Island – a topography familiar to many of us as the mountainous and foreboding terrain that formed the scenic backdrop for the Lord of the Rings Trilogy.

In the 19th-century, Scottish farmers – familiar with the harsh topography of the Scottish Highlands – settled easily in the rugged high-altitude foothills of the imposing mountain range of the Southern Alps – running like a great spinal column down the center of the South Island (S I). For them this was as close to the homeland they had left as anywhere on the globe. Their sheep farming heritage easily transplanted into this new setting.

Like the Scottish Highlands, the S I’s high-country land is poor – expansive high-altitude grassland. With the granite bedrock only a couple of inches below the surface the land is completely unsuitable for arable farming. This landscape is only suitable to the particular Marino breed of sheep – a scrawny bread – bred not for the succulence of its meat but for the fineness of its wool – wool today much coveted by the Italian textile and designer fashion houses. The Italian fashion industry is the end destination for my nephew’s wool.

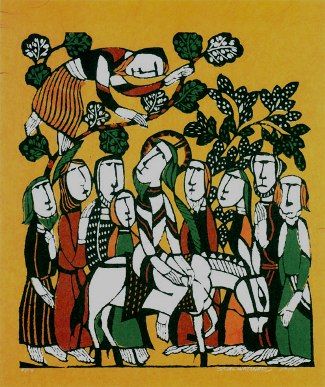

Easter IV draws its Good Shepherd theme from John’s presentation of Jesus as the good shepherd in chapter 10 of his gospel. Here we are given two contrasting images of Jesus. One is as the personification of the good shepherd- I am the good shepherd – hearing my voice my sheep know me and follow me. This image resonates with intimations of intimacy and loving care. The other image – which is the one presented to us on Easter IV in year 1 of the Common Lectionary – is the more striking image of Jesus as the gateway to the sheepfold.

Facing the blank looks of incomprehension on the faces of his disciples as he speaks about himself as the gatekeeper who guards against the illicit entry of thieves and rustlers seeking to mislead and steal the sheep, Jesus offers what I would have thought was an even less comprehensible metaphor – of him as the literal gate to the fold –I am the gate for the sheep.

On a baptism Sunday, the shepherd and sheepfold metaphors present us with fundamental questions about the nature of the church and the dynamics of belonging. What is the Church; how do we get into the Church, and what are the hallmarks of belonging???

The Episcopal Church has this quaint phrase to identify one of its three main membership criteria. Following John 10 you might think the Episcopal Church would say that one of the core attributes of membership is to know and be known by Jesus. It is very telling that the Episcopal Church prefers to define membership as those who know and are known to the treasurer. Easter IV being a baptism Sunday here at St Martin’s – lends an added poignancy to questions of belonging.

The Church is the Christian community – which may seem an obvious statement. But we have a very impoverished understanding of Christian community because we imagine that we are the Christian community – that without us there is no Church. IN this sense we think of the Christian community as a voluntary association much like being members of the tennis club. Accordingly the answer to the question what is the Church – is – we are the Church – the fruit of our organization.

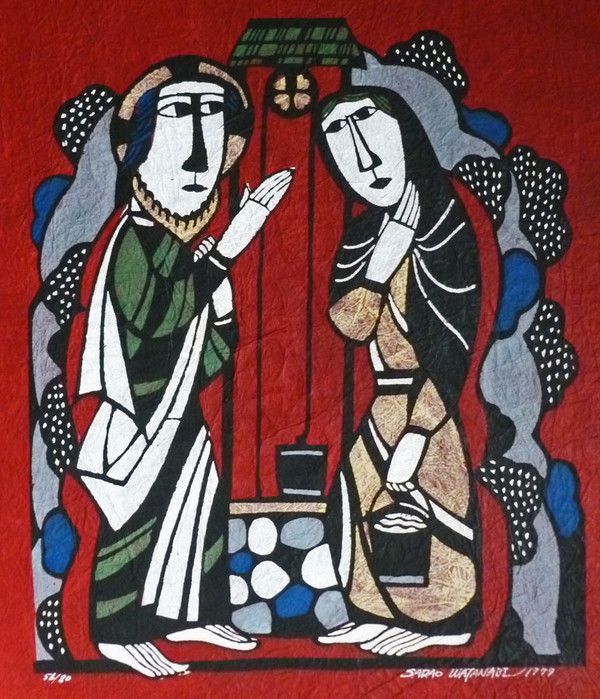

However, the Christian community is God’s creation not ours. The Christian community is not a manifestation of our social organizing. It is the creation of God-in-Christ active within the dimension of time and space. Following this view, we don’t create Christian community – we simply participate in it. As the sheep entering the sheepfold – so we come into a divine community that is already awaiting our arrival and in which we are invited to participate.

That the Christian community emerges from our self-organization is only the first of two major mistaken ideas. The other widespread mistaken view is that being Christian is an individual thing – as in – you don’t need to go to church to be a Christian – or I’m spiritual but not religious. We each can be as autonomously spiritual as we like, but being spiritual does not make us Christian. The Early Church father, Tertullian summed it up when he said one Christian is no Christian. The only way to be a Christian is to participate in the life of the Christian community – which is the divine community of God-in-Christ or the Body of Christ – made visible in the dimension of time and space.

John 10 speaks of both sheep and sheepfold. The sheep don’t form the sheepfold – they enter the sheepfold when they pass through the gate. Likewise, we don’t form the Christian community, we enter the Christian community – the Body of Christ in the world – through the gate of baptism. If baptism is the gate, the rich pasture is the Eucharist. Through baptism we come to belong to a community that nurtures us with the rich pasture of the Eucharist – Christ’s mystical body – upon which we feed.

If John 10 is the metaphor for our entry and belonging within the Christian community then the first reading from Luke-Acts chapter 2 clarifies the nature of belonging. We don’t simply belong by virtue of becoming members – the hallmark of belonging is participation – active engagement in the covenanted relationship with God – and – more challengingly, a covenanted relationship with one another.

By covenanted relationship I mean a relationship in which we become responsible for one another. We read in Acts 2:42 that the first Christians devoted themselves to the apostles teaching and when they gathered to worship God, they broke bread with one another – praying unceasingly for one another, and for the world around them that often viewed them with considerable hostility. In addition, they practiced common fellowship which meant they shared their material resources – holding all things in common for the benefit of all. It’s this characteristic of early Christianity that not only facilitated the Church’s astonishing growth in a short span of time – and day by day the Lord added to their number – but has continued to inspire a vision of a society where each gives according to their ability, and each receives according to their need.

Through baptism we enter into belonging. By participation our belonging fosters believing – both signs of our taking responsibility for one another.

That we seem even further away from being able to embody this ideal as the hallmark of our participation together within the Christian community – is a continued matter for our profound repentance.