The only certainty in life is change. Opportunities arise, and challenges are confronted—some overcome, and others accommodated as we learn to live with what we cannot control. The other great certainty in life is the passing of time. Time passes, memories accrue, future expectations arise, while present-time successes are celebrated, and disappointments are weathered.

The future is unpredictable because however we imagine it, the sorry truth is we just don’t know what it will bring. Uncertainty leads us to hold two conflicting illusions at the same moment—that change can be resisted by turning back the clock and that time flows only in one direction, from past to future, and not the other way around. Advent is a season for the contemplation of change – signifying God’s intrusion, disrupting the smooth running of our broken world by playing fast and loose with the linear flow of time. Advent’s message speaks of new beginnings and ultimate endings in the same breath. Only in the depiction of the ending is the deeper meaning of the beginning revealed.

In a recent piece for Christian Century, Brian Bantum noted the difference between our experience of time and God’s—the feeling of being stretched between past, present, and future—akin to singing a song where the words we’ve just sung are still in our mind as we sing new words in the moment—anticipating the words still to come.

Bantum notes that we live in a current of time that flows like a great river of being within God’s life. For us, time is segmented and linear. For God, past, present, and future could be imagined as braided together, flowing like drops moving and twisting in a river.

Advent Sunday in 2024 coincides with the commemoration of Nicholas Ferrar, who, in 1625, in a place called Little Gidding – a tiny hamlet on his family estates in Huntingdonshire northeast of Cambridge – formed a small religious community centred on a disciplined life of prayer, work, and pastoral care modelled on the liturgical heart of the daily offices in the Book of Common Prayer. In 1941, the poet T.S. Eliot – in the depths of war-time winter, made a pilgrimage to the church at Little Gidding with the memory of Ferrar’s brave little community very much in mind.

In the final quartet, Eliot reflected on this visit, appropriately titled Little Gidding of his Four Quartets. Here, he articulates the multidirectional interplay of past, present, and future. He challenges the notion of time as only linear, with a single flow of direction flowing from the past to the future. For example, he wrote, We shall not cease from exploration/ And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started/ And know the place for the first time.

If the past is memory and the future expectation, the present time is opportunity. Advent, if seen as only a future-oriented expectation, runs the risk of consigning the present to a period of passive waiting for the real action to begin. Advent becomes rather like sitting in the cinema, playing with our phones as the ads and previews play – distractedly anticipating the imminent arrival of the main feature. Seen like this, Advent becomes a period of marking time – a season marked by passivity – as the possibility and opportunity pass us by unnoticed. Future-oriented expectation has only one purpose – that is to guide and shape the actions we are called upon to take now.

There’s that time-honoured saying most recently placed in the mouth of Sonny, the manager of the Exotic Marigold Hotel – when seeking to offer reassurance, he says that everything will be OK in the end—if it’s not OK now, that means it’s not yet the end.

But Sonny’s advice is a false comfort. Today, things are not OK – in fact, things are very far from being OK in our world! We wait passively – enduring the evils around us in the reassurance that things will all work out in the end? We look toward future expectations while missing the more important question of what do we need to be doing now? If we wait for our future expectations to come to realization we miss the point of them because the purpose of our vision of the future is to guide and energize our actions in the present. Our expectation of the future is realised in our actions in the present time.

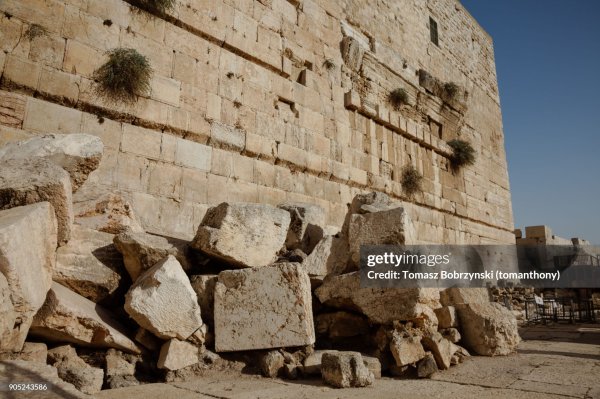

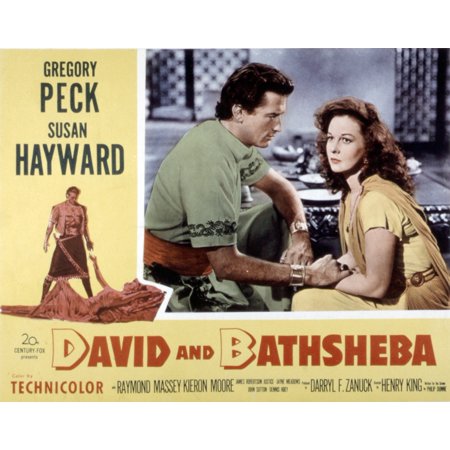

Jeremiah predicts the fulfilment of God’s promises as future event. The past becomes realized only as future fulfilment. In projecting the past into the future like this, he seems to leapfrog the present. But perhaps this is understandable. The Babylonians are at the gates of Jerusalem. Destruction and exile seem the most likely outcomes, and maybe Jeremiah can be excused for skipping over the present – facing an impending catastrophe, there is nothing to be done. Yet, although not recorded in this passage, Jeremiah does have a sense of the importance of present-time action. Imprisoned in the palace guard room as the hostile army masses at the city gates – he instructs his scribe to exercise a purchase option on a piece of family land. Amidst the impotence of crisis – Jeremiah still believes in a future he will not live to see. The purchase of land he will not live to enjoy is still planting a marker of resistance to fate in the earth.

In Luke 21:25-36 Jesus shows us a vision of the ultimate fulfilment of the journey that must begin with his birth. Despite predictions of fear and woe – in the parable of the fig tree, he draws our attention away from future speculation to the necessity to act now. The fig tree’s leafing is not a future expectation of summer to be passively awaited but a recognition that summer has already arrived, demanding an action response now. The intrusion of God’s kingdom is already here. It’s now time to act.

Advent is a time for the expectation of things to come as an inspiration to plant in the present time the seeds that will one day mature into our future hope. Advent means consciously rejecting the self-protective foreboding and striking out with courage to boldly embody our future expectations because they are already effective within us.

In memory and imagination, time flows back and forth. Past mistakes are mitigated by present-time action. Future expectation – while still only potential becomes realized not in waiting but through action in the here and now shaped by the anticipation of its arrival.

The novelist Alice Walker wrote we are the ones we have been waiting for. My question to us this Advent is – are we not already the people we have been waiting to become?