Image: Andrei Rublev’s 15th-century icon of the Holy Trinity

Last week on Pentecost Sunday, I likened the Bible to what my granddaughter Claire, at an important stage in her learning to read, used to refer to as her chapter books. When children are learning to read, a critical stage is reached when they graduate from simple, single-storyline books to complex stories that unfold in stages, or chapters. In the last two weeks, we have celebrated two significant chapters in the Christian biblical chapter book- namely the Ascension of Jesus and the descent of his Spirit – a two-way process which Tom Wright describes as the moment when the personal presence of Jesus with his disciples is translated into the personal power of Jesus in his disciples.

Pentecost is the final chapter in the Christian chapter book. But in all good chapter books, the final chapter is often capped off with an epilogue – a short addition or concluding section at the end of a literary work, usually dealing with the future of its characters. Trinity Sunday is the Christian chapter book’s epilogue, hinting at a foretaste in volume two, so to speak, of the continuing Christian storyline with the action now centering on the life of the Church.

How do you recognize an Episcopal Church at first sight? Well, the red doors are usually a giveaway. But when you see Holy Trinity as the dedication of the church, you know this is an Episcopal Church. The Trinity is deeply revered in the Anglican tradition with by far, a greater number of Episcopal churches dedicated to the Holy Trinity than to any other single dedication. Why is this so? I think it must have something to do with the naturally speculative cast of the Anglican mind. Unlike more literalist traditions, we appreciate mysteries to puzzle over. We’re not interested in simple answers to complex questions. We appreciate mystery as something that hints at but never fully explains truth.

There is a spoof report of a supposed conversation between Jesus and his disciples. In answer to Jesus’ question Who am I? Peter, – yes, it’s always Peter who pipes up first – launches into: “Thou art the Logos, existing in the Father as His rationality and then, by an act of His will, being generated, in consideration of the various functions by which God is related to his creation, but only on the fact that Scripture speaks of a Father, and a Son, and a Holy Spirit, each member of the Trinity being coequal with every other member, and each acting inseparably with and interpenetrating every other member, with only an economic subordination within God, but causing no division which would make the substance no longer simple”. And Jesus answering, said, “What?”

Some people are, by temperament, Jesus-people. Others by temperament are God-people, while others, often many others, are Holy Spirit-people – no, I’m not looking at Linda+ when I say this. I have to say I appreciate the role both Jesus and God play in my spiritual imagination. I’m also good on the Holy Spirit as long as we don’t get too enthusiastic about her. But my temperament really hums in the contemplation of the Trinity. Why is this? Part of my answer would be to affirm the elegant simplicity of the Trinity as the fullest expression of God. And I want you all to know how simple and enticing the Trinity really is.

The distinctively Christian understanding of God, as Trinity, emerges from the Pentecost event, as an everyday experience long before it became a doctrine. This unthought experience of God as Trinity is captured in a venerable Celtic prayer:

Three folds of the cloth, yet only one napkin is there, Three joints in the finger, but still only one finger fair, Three leaves of the shamrock, yet no more than one shamrock to wear,

Frost, snowflakes and ice, all in water their origin share,

Three Persons in God: to one God alone we make our prayer.

Like most experiences, it’s only when we turn our backs on the poetic and try to rationally capture the intuitive that things get complicated.

God as Trinity – that is, as divine community – arose out of the everyday experience of the first Christians. They knew of God, the creator, from their Jewish inheritance. Yet, this inheritance of faith had been augmented through a collective memory of Jesus as a human personification of God. Following the Ascension event, when they had so keenly felt the loss of a personal connection with Jesus, at Pentecost they became overpowered by– literally inflated with his Spirit as the personal presence of Jesus with them was translated into the personal power of Jesus in them. It’s only later, when Christianity takes root among the Greeks – ah those Greeks being of a more philosophical frame of mind, loved codified statements – like the one we repeat every Sunday in the Nicene Creed. It’s here that the Trinity begins to get complicated.

While human beings have always cherished relationships, it’s only with the advent of a psychosocial understanding of relationship that we have grasped the importance of relationality as the engine of emotional development. Following on from our being created in the image of an unseen God, we can deduce that the dynamics at play in human relationships reflect something essential about God. If we are made for relationships in community then might this be true of God as well. The image of God as a solitary being falls away before the image of God as divine community.

I’m now coming closer to answering the earlier question of why I am at heart a Trinity-person. In 2025, the celebration of the Holy Trinity coincides with both Father’s Day and the baptism of a child in the fourth generation of one of our church families. Both Father’s Day and baptism provide rich material for reflecting on the relational nature of God as divine community.

Fatherhood, often thought of as a male characteristic – the possession of individual men, is really a concept dependent on and expressive of relationship. All fathers are men, but not all men are fathers. Men become fathers only through the procreation or adoption of children. Relationally speaking, you cannot be a father without a child.

Traditionally, despite acknowledging that God is genderless, God the creator nevertheless has been referred to as Father, rendering Jesus his Son. Yes, these are now unfashionably gendered nouns. But its not the gendering, but the relationality of these nouns that captures the essence of the divine nature. Other nouns for God can be used so long as they speak of relationship – as in Lover, Beloved, and Love-sharerer. As with us, so it seems with God. Fatherhood is an identity created through a relationship. Likewise, baptism speaks the language of relationship.

Here, a contemporary psychological understanding of relationality is pertinent. Human beings come into existence through relationships. I’m not referring here to biology but to the development of self-consciousness as the core foundation for identity.

The psychology of Object Relation Theory, the psychoanalytic school in which I was trained as a therapist after my ordination to the priesthood, perceives the infant as object-seeking from birth. This means the infant is instinctively drawn to the mother, initially to her breast, but soon her face as well. Every mother of a newborn knows this unfolding experience. The infant and mother are held in the embrace of a mutual gaze. It’s the experience of coming to self-consciousness through the gaze of the mother that is as vital to infant flourishing as the physical sustenance the mother provides.

My point in all of this is to say that our sense of self is caught – a process of self-discovery through catching a glimpse of ourselves in the gaze of another. Self-consciousness and identity are the fruit of being in relationship. While the initial mutual gaze is between mother and infant, it eventually broadens to include the gaze between mother, father, and infant as the child develops a consciousness of the father’s presence.

I want to make a necessary disclaimer here. Although I’ve been speaking of the more usual context of female mother, with male father, I want to stress that mothering or motherhood, fathering or fatherhood are potentially gender fluid roles. However, this takes us into a more contested area and should be the subject of a separate sermon.

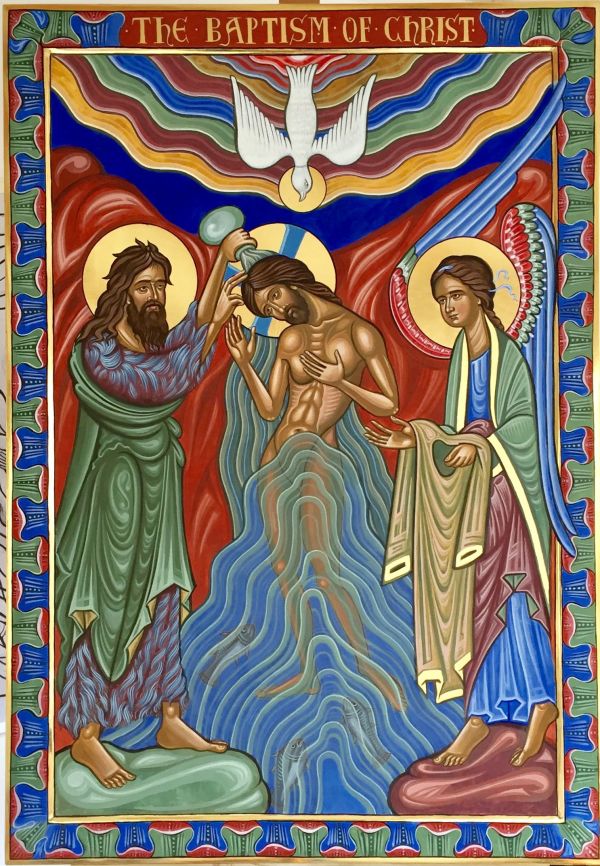

I’ve been suggesting that the Trinity is first an experience and only thereafter a concept of God as relational within divine community. This seems a somewhat modern development in reinterpreting traditional metaphors for God, yet, the early 15th-century Russian iconographer Andrei Rublev seems to have had a premonition of God as a divine community that uncannily echoes a contemporary, psychologically informed image of God.

His icon of the Holy Trinity depicts three angel-like figures seated around a table – an allegory of the visitation of the three angels to Abraham at the oaks of Mamre as recorded in Genesis 13. But it’s the facial expressions I want to draw your attention to. Although dressed differently, and presented essentially as men – although angels are actually genderless, they share the same face and gaze through the same eyes. Their mutual gaze of love is evocative of the gaze shared between mother and infant. It’s as if each is held in being through the exchange of mutual gaze with the other. The optical illusion is created so that while the members of the divine community sustain each other through a shared loving gaze, we are also drawn into the experience of that gaze. Before Rublev’s icon of the Holy Trinity – we experience something so familiar to us – an echo from our earliest unthought memory.

Today, on Trinity Sunday, little Evie Tulungen will become a Christian. This is a shorthand way of speaking. But exactly in what sense will Evie become a Christian? Most of us will imagine that Evie becomes a Christian through the flowing of water and the anointing of the Holy Spirit. Both are true. But what we may miss is an equally important point. It will be through her baptism that Evie becomes a part of the mutual gaze shared between participants in the Christian community. The Early Church Father, Tertullian is reputed to have said that one Christian is no Christian. What he meant was that being Christian, like fatherhood and motherhood, like sonship and daughterhood, is a relational experience. There are no individual Christians, only persons who through baptism are born into a shared life of relationship within a community called Christian. Though an imperfect reflection it may be, the community of the Church is none other than the reservoir for a love no longer exclusive to the Divine Community but now shared through the overflowing of the Spirit into the life of the world.