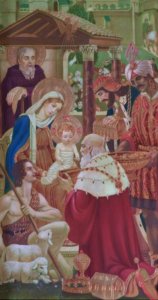

Image: The dream of St Joseph. Bernardino (Bernardino de Scapis) Luini (c.1480-1532)

This year, we return to Matthew as the gospel of choice in the three-year Lectionary cycle. Thus, Advent IV’s gospel opens with Matthew’s account of the events leading to the birth of Jesus. Matthew structures his birth narrative around themes specific to him. I want to offer a very personal take on Matthew’s understanding of the significance of Jesus’ birth.

For most of us, our sense of the nativity narrative emerges from an often unconscious compilation of Luke and Matthew, giving us the typical manger scene depicted in countless churches and nativity plays. In doing so, we miss the significance of each Evangelist’s distinctive portrayal of the events surrounding Jesus’ birth.

Luke’s focus is on Mary. His birth narrative is Mary’s story, depicting a birth in farmyard conditions surrounded by sheep and cattle and witnessed by ordinary shepherds – representative of those on the margins of society – and of course, let’s not forget the angels.

Matthew’s version of events gives us Joseph’s story – the story of Jesus’ birth told from Joseph’s perspective. Matthew does not mention the setting. Here, there are no shepherds, no cattle or sheep. This is a birth witnessed not by ordinary people but by foreign emissaries – the Magi – representatives of the wider world’s homage to the infant king of the Jews. Matthew also has an angel, but Matthew’s angel appears not to Mary, as in Luke’s account, but to a dreaming Joseph.

The first point to notice in the Matthew chronicle is the importance of establishing Jesus’ identity within the long genealogy that extends back through Jewish mythological time to Abraham. Matthew spends 17 verses of his 25-verse first chapter to do this. So we notice from the outset how intensely a Jewish story this is.

The second point to note is that Matthew’s story is highly political, situating the birth of Jesus within the turbulent political context of 1st-century Palestine. Here we have all the ingredients for a tense political drama – a brutal ruler in Herod the Great, the puppet of Roman occupation, whose murderous intent drives the Holy Family into exile as political asylum seekers. The Holy Family escapes, but every other-year-old male child born in the region of Bethlehem is slaughtered as Herod, alerted by the indiscretion of the Magi, endeavors to neutralize Isaiah’s prophecy of the birth of a rival king.

Matthew’s is a rich narrative, one that sets the birth of Jesus within a political context entirely familiar to us today in a world where literally millions of fathers and mothers with young children are daily forced to undertake the perils and dangers as refugees escaping in fear for their lives. And, Matthew’s birth narrative provides a contemporary flavor of the political and humanitarian themes embedded in his account. Matthew sets Jesus’ birth within the context of political oppression and of a ruler’s desire to seek out and punish anyone who poses a threat.

Matthew’s birth narrative also hints at the societal complexities of Joseph and Mary’s predicament. Matthew will go on to describe the holy family’s displacement and flight from political violence, but he must first skillfully navigate 1st-century Jewish societal reactions to surprise pregnancies out of wedlock.

Matthew’s approach to the Jesus story is told from within the Jewish patriarchal worldview of the men in charge. I have an intense personal unease with this feature of his approach. As a gay man, I learned early to fear the power of the patriarchy and to be deeply suspicious of the presentation of scripture through the exclusive lens of the men-in-change, in whose worldview there was no place for someone like me.

Richard Swanson is – at least to my way of thinking – a delightfully provocative biblical commentator who never misses an opportunity to take the patriarchal voice – that is, the traditional interpretation of scripture from the restrictive perspective of the men-in-charge – down a peg or two. Swanson coined the delicious phrase Holy Baritones to describe scripture’s patriarchal voice. My not infrequent uneasiness with Matthew’s voice is that, at times, he seems to me to epitomize the role of section leader in the Holy Baritone chorus.

It’s only in verse 18 that Matthew turns to the birth of Jesus. Having, as I’ve already noted, spent the first 17 verses of his 25-verse first chapter establishing Jesus’ identity at the heart of Jewish patriarchal transmission. Matthew writes:

When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child.

In a society with a strict prohibition against sex before marriage, which by the way is a central convention in all patriarchal societies, including our own until relatively recently, Matthew chooses to introduce the birth of Jesus by telling us that Mary was found to be with child.

Was found to be is a grammatical structure known as the divine passive. It’s a way of telling us that so and so happened while obscuring causality. For the Hebrew writers, it was a way of indicating that something had occurred by the hand of God without invoking the name that could not be spoken. Matthew makes clear that Mary’s pregnancy is the result of God’s hidden hand. Still, unlike Luke’s portrayal of a direct encounter between Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, in which God addresses Mary directly and respects her primary decision-making agency, the thrust of Matthew’s narrative suggests that, once Mary’s pregnancy is discovered, she no longer has any agency, with all decision-making reserved to Joseph.

Matthew presents Joseph in a predicament. His reputation, through no fault of his own, is endangered by this turn of events. A kindly middle-aged widower with a teenage betrothed, he is resolved to end the engagement quietly. What a mensch! But here’s my problem with Matthew’s Joseph-focused version of events. In a religious society with draconian laws against sex before marriage, Joseph’s risk is one of public disgrace. Still, Mary risks honor killing by being stoned to death – in the first instance by her father – and if he could not bring himself to do the deed, then by another male relative – an uncle, or brother, or male cousin conveniently waiting in the wings. The reality of honor killing is a nasty detail that the Holy Baritone voice skips over in silence.

So how is Joseph to be extricated from his predicament of being betrothed to a girl who has now been found with child. Matthew rescues Joseph through the tried and trusted literary device of an angel appearing to him in a dream, telling him not to be afraid. Afraid of what we might ask? – if not a reputational disgrace. The angel instructs Joseph to proceed with the marriage because it is God who has caused Mary’s pregnancy. On waking, Joseph dares to do as the angel had commanded him. After all, what’s social opprobrium when compared with divine displeasure?

We might expect Matthew to end his chapter here. Joseph the mensch rescues his betrothed by marrying her. But as a cheerleader for the Holy Baritone voice, Matthew is not done yet. He rather tellingly – to my mind at least – mentions that while Joseph married Mary, he declined to consummate the marriage until after the child was born.

Why does Matthew feel the need to tell us this? Well, one of the pervading themes of the Holy Baritone voice is a preoccupation with genital penetration and sexual purity. As today’s conservative obsession with the restriction of women’s reproductive, queer, and transgender rights continues to demonstrate, this preoccupation continues a story older than time.

Let’s listen again to Matthew’s voice:

When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son, and named him Jesus.

Although Joseph did as he was commanded, we will never know how he actually felt; however, we have a hint of how Matthew thought he might.