Last Sunday after the Epiphany – 2026

We stand at a hinge in the liturgical year. Behind us lies the season of Epiphany with its moments of illumination. Ahead of us stretches the long road to Jerusalem and the austerity of Lent. At this pivotal point in the Jesus narrative, we are given two mountain stories: Moses on Sinai and Jesus on the Mount of Transfiguration. Two peaks. Two luminous encounters. Two moments when heaven and earth appear to overlap.

Across the wide sweep of Scripture—from Moses to Jesus—we can trace not a change in God, but a deepening in human awareness of God. For Moses, God is encountered “up there” and “out there”—in thunder and cloud, in fire and trembling mountain. God commands wind and sea. The divine presence is external, overwhelming, transcendent.

By the first century, something has shifted. The prophets speak of a law written on the heart. The psalmists cry from the depths of inward experience. By the time Jesus appears, God is no longer encountered only on mountains but within conscience, compassion, and community.

The movement is from “up there,”

to “in here,”

to “between us.”

This is not a movement from transcendence to its absence, but from transcendence as distance to transcendence as depth.

Charles Taylor describes a similar shift in Western consciousness. In A Secular Age, he speaks of the transition from an enchanted world to a disenchanted one. In 1500, belief in God in the West was nearly unavoidable. The world felt charged with spiritual presence. Today, belief can feel implausible. Reality appears calculable, controllable, confined.

In an enchanted age, transcendence saturates reality. In a disenchanted age, reality is saturated with immanence. We have descended from expansive connectivity into increasing isolation.

And yet the hunger for transcendence persists. We binge stories of magical realism. We attend concerts like revivals.

We chase peak experiences. We curate spiritual moments. The longing has not disappeared. The human spirit still yearns for more than what can be measured.

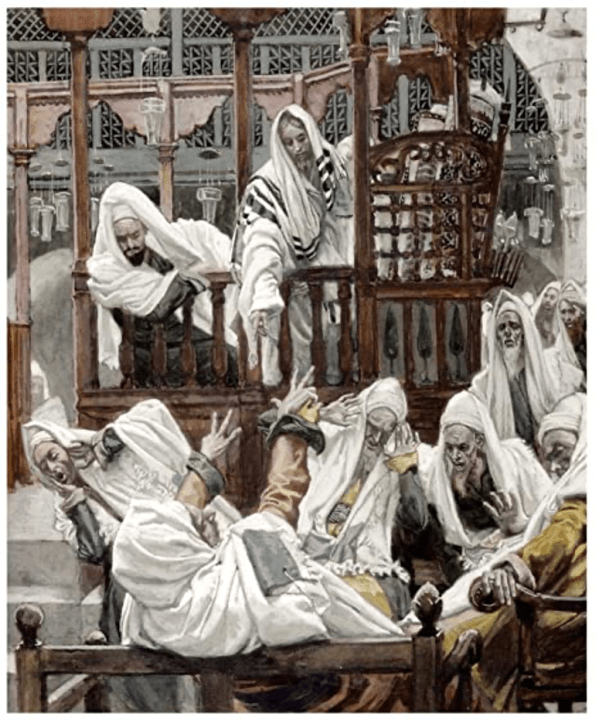

On the mountain of Transfiguration, Peter sees Jesus radiant, his face shining, his clothes dazzling. Moses and Elijah appear. The veil between material and spiritual reality thins. Time itself seems to bend. In response, Peter cries out:

“Lord, it is good for us to be here. Let us build three dwellings.”

He wants to contain the moment, to hold it in place, to domesticate transcendence within the structures of control.

But the cloud descends. The voice speaks. And just as suddenly, it is over.

As they descend, Jesus orders silence: “Tell no one about the vision until the Son of Man has been raised.”

Illumination and secrecy. Now—and not yet.

But why secrecy?

Because revelation without readiness can distort.

Because glory without the cross becomes fantasy.

Because peak experience is never the destination—it is only ever a preparation.

The mountain is not a residence. It is a revelation.

The Transfiguration is a moment when the spiritual penetrates the material, allowing Jesus and his disciples to see more clearly the path downward and onward.

We often imagine transcendence as altitude. But altitude is a primitive religious metaphor.

When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. declared, “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” no one assumed he had taken a hike. The mountain had become a metaphor for moral clarity, prophetic vision, the ability to see beyond present injustice toward promised possibility.

Transcendence is not about geography. It is about perception. And here lies the paradox for us in 2026: in a disenchanted age, transcendence is not found by escaping immanence. It is discovered within it. Not somewhere else. Right here.

The distinction between joy and happiness helps illuminate this.

Happiness is self-focused.

Joy is self-transcending.

Happiness asks, “How do I feel?”

Joy asks, “Who can I share this with?”

Joy and grief are closer than we imagine. At births and weddings, at funerals and memorials, we are carried beyond ourselves. In deep grief, we transcend the self just as surely as in deep joy. We are bound to others in shared vulnerability. Both joy and grief rupture the illusion that we are alone on center stage. Both are moments of transcendence that reconfigure our experience at the very heart of immanence.

In recent days, the people of Minneapolis have experienced something that, in its own way, bears the shape of transfiguration. Moments of crisis have catalyzed protest. Protest has coalesced into collective resistance to power. In those moments, something happens “between us.”

Strangers stand together.

Voices rise in chorus.

Fear and courage intertwine.

Grief and determination occupy the same streets.

No one would call such days “happy.” Yet they are transcendent. In the face of injustice, people move beyond private preoccupation. They step off the lonely center stage of individualism and into a web of shared vulnerability and resolve. Community, no longer theoretical, becomes embodied.

Ordinary streets become sites of moral clarity. Immanence becomes the arena of transcendence.

Not dazzling light on a mountaintop,

but illumination in the midst of pain.

Not escape from history,

but deeper engagement within it.

This, too, is transfiguration!

The disciples glimpse glory. But they must descend the mountain back into ordinary existence. They have glimpsed who Jesus is. But they must walk with him toward who he must become.

The Transfiguration is a hinge moment. Behind it lie teaching and healing in Galilee. Ahead lies the costly solidarity of Jerusalem.

Behind us is the light of Epiphany. Ahead lies the demanding honesty of Lent that will strip away illusion, confront us with suffering, and challenge our need for distraction.

But today we are given a glimpse—so that when darkness comes, we remember that Transcendence is real, not as escape, but as empowerment to live in the present moment – to face its challenges and to embrace its opportunities.

The thread that binds Moses, Jesus, Charles Taylor, Martin Luther King Jr., Minneapolis, joy and grief together is this:

Transcendence is not about leaving the world.

It is about seeing the world differently.

It is not about climbing higher.

It is about loving deeper.

It is not found in isolated bliss.

It is found in relational courage.

God is not only “up there.”

Not only “in here.”

But “between us.”

In the space where we risk connection. Where grief becomes solidarity. Where solidarity transforms hope, Jesus does not remain on the mountain. He touches the frightened disciples and says, “Get up. Do not be afraid.” Then he sets his face toward Jerusalem—toward suffering, service, and a love that does not retreat.

“Listen to him,” the voice from the cloud commands.

And what does he teach?

Blessed are the poor.

Blessed are the peacemakers.

Love your enemies.

Lose your life to find it.

This is transcendence within immanence. Glory revealed in vulnerability.

In a disenchanted age, we are tempted either to chase spectacle or to surrender to cynicism. The gospel offers a third way.

Attend to the relational space.

Stand together in grief.

Serve in love.

Resist injustice.

Practice courage.

Transcendence has not vanished. It has simply moved.

Not up there.

Not someday.

But here.

Now.

Between us.

The mountain shows what is possible.

The descent shows who we are becoming.

As we enter Lent in 2026—with political fractures, digital distraction, ecological anxiety, and spiritual weariness—the invitation is not to escape upward. It is to descend with purpose to discover that even in a disenchanted age, the world still burns with unconsumed fire—if we have eyes to see and ears to listen.

And so we listen.

We rise.

We walk down the mountain—together!