Our lives unfold inside stories.

Whether we are conscious of it or not, our experience of living in time and space is structured by the stories we tell—about ourselves, about one another, about the world, and about God. It is through story that the world takes on shape and meaning, that chaos becomes intelligible, that suffering is given context, and hope a horizon.

So the most important question we can ask about the stories we tell is not whether they are true or false, but whether they are big enough.

Are they thick stories—or thin ones?

Thin stories are easy to tell. They reduce complexity. They trade nuance for certainty. They divide the world neatly into winners and losers, insiders and outsiders, saved and lost. They are efficient. They are emotionally gripping. And for a while, they feel powerful.

But sooner or later, the threadbare nature of thin stories becomes increasingly difficult to hide. When reality refuses to fit their narrow frame, thin stories resort to fear, coercion, and eventually, violence to hold themselves together. Thin stories always need enemies.

Thick stories, by contrast, are harder to tell and slower to hear. They are woven from many strands—memory and hope, failure and grace, belonging and struggle. They leave room for contradiction and growth. They make space for human flourishing because they are large enough to hold real lives.

It is the thickness of our stories—their depth, complexity, and generosity—that determines whether we thrive.

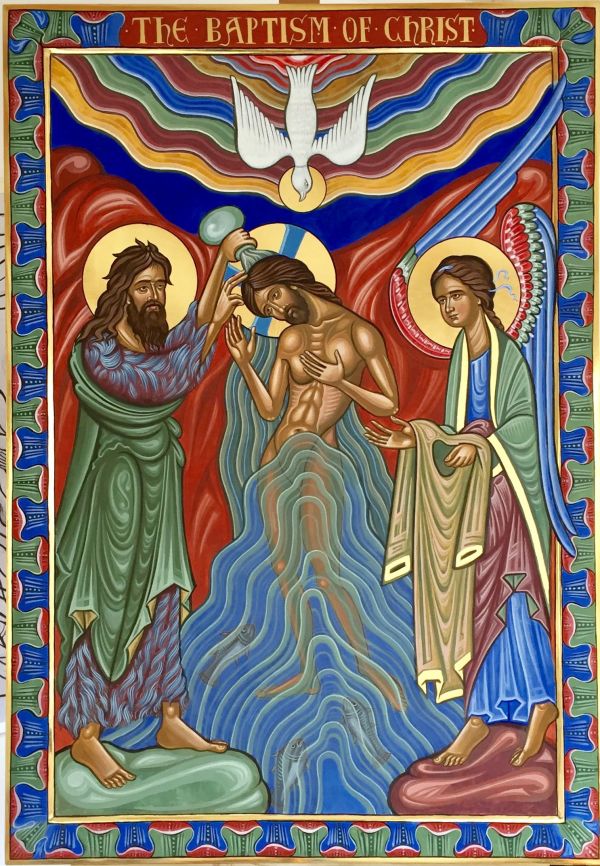

And today, we stand inside one of the thickest stories the Christian faith knows: the baptism of Jesus. And in 2026, we inhabit this rich story surrounded by the fraying of the thinnest of national thin stories.

All four Gospels tell a story about Jesus’ origins—but they do so in strikingly different ways.

Matthew and Luke begin with birth stories. Mark begins abruptly, with no mention of an infancy at all, Jesus emerges from the long silence of childhood and adolescence and steps onto the public stage as a grown man, ready to begin the work God has given him. John reaches back even further, telling a cosmic story of pre-existence: the Word who was with God and was God from the beginning has taken flesh and blood.

Each Gospel tells the same truth—but not in the same way. Each shapes a recognizable yet distinctive identity through story. This is the variety offered by a thick story – the truth -approached from a number of different angles.

And that matters, because identity is always a moving target. We discover and rediscover who we are through the stories that are told about us—and as these stories become our own, edited and reedited to become the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and the world we inhabit.

Some identities are rooted primarily in birth. For a few—royalty, dynasties, elites—birth alone bestows belonging and meaning. But for most of us, identity is shaped less by birth than by adoption.

We become ourselves through a series of adoptions: into families, friendships, communities, vocations, causes, and commitments. Each adoption draws us more deeply into the persons we are becoming.

That is why baptism matters.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke recount Jesus’ baptism differently—and their differences reveal something essential. In Matthew’s and Luke’s birth narratives, the divine nature is conceived in human gestation. Matthew’s account is typically shorn of the human warmth of Luke, an event reserved only for the select few, whereas in Luke, Jesus’ baptism is witnessed by the crowds – a solidly communal experience. But it’s in Mark’s account that Jesus’ baptism becomes intensely personal. In Matthew and Luke, the heavens majestically part, but in Mark, they are violently torn open. In all three accounts, the Spirit descends, and the divine voice proclaims, but in Mark alone it is a voice heard only by Jesus. It’s personal, it’s particular, it’s the voice of divine adoption – still a secret only to be shared between Jesus and God.

These are not contradictions. They are complementary truths held together within a thick story. Within the complexity of this thick story, a key question remains unanswered. Is baptism a personal or a communal event? Is baptism the certificate of individual salvation —or is it the recognition of entry into the life of a community that is already saved?

The Christian tradition has never settled this question neatly, because it refuses thin answers to complex questions. What baptism does is tell us where and to whom we belong.

Jesus’ baptism echoes the first story of creation, when the Spirit of God swept over the waters and breathed life into the world. At the Jordan River, that same breath rests upon Jesus. God claims him. Names him. Delights in him.

And why the adoption strand in Mark’s account is crucial is that it shows that what God does for Jesus, God does for us.

As Jesus is baptized into a relationship of adoption, so are we.

In baptism, God adopts us—not because we have earned it, not because we understand it, but because God delights in us. Before we believe, before we choose, before we behave correctly, we are named and claimed.

Belonging precedes believing!

This is where the Christian story confronts the thin stories of our time.

Our nation is struggling—violently at times—to tell a story about who belongs. Immigration, race, power, identity, and fear have all been reduced to brittle slogans and hardened boundaries. Thin stories dominate because they promise certainty in an anxious world.

But many of us no longer recognize ourselves in these stories. We sense—often without knowing how to articulate it—that they are too small, too cruel, too narrow to hold the truth of our lives together.

What we are witnessing is not merely political conflict. It is a struggle over belonging.

Which story will tell us who we are and where we belong?

The Christian story is very thick, yet this does not mean the Church is immune to thin interpretations.

Different Christian communities tell very different stories about baptism, salvation, and belonging. Some see baptism as a personal declaration of faith—a transaction securing one’s place in heaven. Others see it as entry into a tightly bounded institution where salvation is carefully guarded.

The Anglican tradition tells yet a different story—an awkward, sometimes frustrating, but profoundly generous one.

William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury, once said, “The Church is the only society that exists for those who are not its members.”

That sentence unsettles us because it resists thin boundaries. In the Episcopal Church, belonging often precedes believing. People find themselves woven into the life of the community—sometimes long before they know what they believe.

Our boundaries are intentionally fuzzy. Worship is open to all. The invitation to Communion is offered to the baptized—yet no one is turned away at the rail. To some, this seems inconsistent. But it reflects a thick story: the Church as a sign of God’s salvation already at work in the world.

Unlike other traditions, ours does not confine grace. We are content only to witness to it.

Baptism, then, is not a private spiritual insurance policy. It is entry into a community that lives for the sake of the world.

That is why the Episcopal Church places such weight on the Baptismal Covenant. Baptism is not something that happened once. It is something we relive every day.

We promise to persevere in the life of community.

To resist evil and return when we fall and to proclaim—not create but proclaim—the good news that God has already acted.

We promise to love and serve our neighbors. And to strive for justice, peace, and to fight to defend the dignity of every human being.

These promises are not abstract ideals. They are the practices of belonging.

They form us into people who can live inside thick stories—stories that do not require enemies, that do not depend on fear, that make room for difference and growth.

At Jesus’ baptism, God does not give him a task list. God gives him a name.

“You are my Son. With you I am well pleased.”

Before Jesus teaches. Before he heals. Before he suffers. Before he dies. He comes to belong.

Belonging comes first.

And that is the story we are called to live and tell—not only in church, but in a world desperate for stories big enough to hold the hope. And remember Advent’s key message about hope. That for which we hope is already present to us simply by virtue of our hoping. We are already those for whom we have been waiting. So let us stop waiting and proceed with the tasks at hand.

Amen.