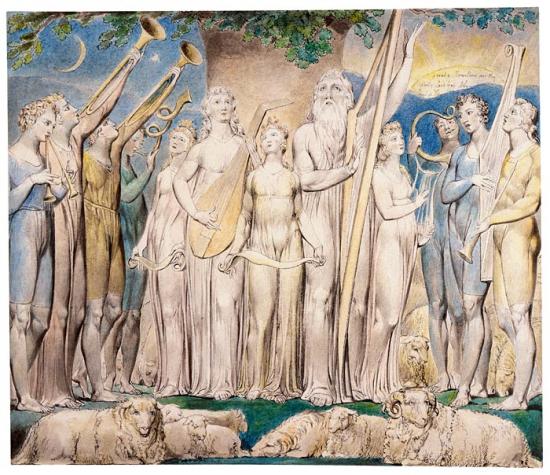

Image: The Book of Job, William Blake

In her sermon two weeks ago, Linda+ introduced us to the recent series of OT lessons from the Book of Job, saying that the much-used statement “Everything happens for a reason” is one of the five cruelest words in the English language to someone who is suffering—right up there with “It’s all in God’s plan.“

I’ve coined the term fable morality for the popular attitude that luck – the avoidance of tragedy in our lives is a sign of God’s grace. Linda+ asked: where are the blessings and the grace of God for your neighbor who has lost everything? You get grace and blessings, and they don’t? What kind of God allows that? What kind of God would do that? She concluded her introduction with Welcome to the Book of Job.

Welcome indeed!

We are mostly familiar with the story of Job – a non-Israelite yet righteous man – whose faith in God is tested in severe adversity. Job is so righteous that God boasts about him in the heavenly council – holding him up as an example of human faithfulness arousing the angelic adversary – the satan’s invitation to enter into a small wager. Here we make a curious discovery – that the Lord God is a bit of a gambler who likes nothing better than a flutter on the forces of fate.

God seems to have allowed himself to be manipulated by the satan with the expectation of a safe bet. Expecting a quick an easy win – the Lord is utterly unprepared for what happens next. At first Job responds as God expects. Twice he refuses to curse the Lord. But then Job does something God didn’t expect – he seeks an explanation as to why his life has taken this calamitous turn. In doing so he appeals to the Lord’s justice as the better side of the divine nature.

Here lies the central theme in the story: Job continues to insist on his righteousness while refusing to acknowledge that the sorry turn of events in his life is the result of sin. Job demands an explanation from God on the basis that the Lord is a just god. In insisting on justice as an essential attribute of the Lord God’s identity, Job exposes God’s betrayal of God’s own better nature.

There’s an old joke among preachers concerning a marginal note in the sermon text that reads – argument weak here so shout and pound the pulpit. From the voice within the whirlwind, God now tries to deflect Job’s questions with a display of pulpit thumping designed to intimidate and silence Job. Pounding the divine pulpit, the Lord roars -who are you to question me? Can you do what I’ve done? Were you there to see my power at creation? Do you know more than I know?

But Job is not questioning God’s power. For Job, God is God not simply because God is all-powerful. God is God because justice is an essential and integral aspect of the divine nature without which God cannot be God.

God begins to realize the bind he finds himself in. He cannot respond to Job in terms of justice because confident of quick victory in his wager with the satan – he has allowed a manifest and brutal injustice to be perpetrated on Job. Thus, God draws the robe of the power around himself – blustering and stomping about in the hope that Job won’t notice that God is changing the subject. Job lies in abject suffering while God waxes lyrical about creating crocodiles and whales.

In Chapter 42:1-6 we have Job’s response. Unlike his earlier speeches in self-defense – Job’s final response is brief and concise. Most English language Bibles use the following translation.

I know that you can do all things and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. I uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know. I had heard of you by hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore, I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes.

All’s well that ends well – in other words with the explicit warning – who are we – mere mortal beings – to question the Almighty? Repentance before the Lord even in the face of what seems inexplicable injustice is the only acceptable response.

However, this traditional interpretation makes no sense and does serious violence to the integrity of Job’s complaint. Jack Miles in his revolutionary book God: A Biography offers a very different approach to interpretation. Miles justifies this by demonstrating how the traditional interpretation relies on a repentance gloss on the original Hebrew introduced in the 2nd-century Greek translation in the Septuagint. After his long and passionate presentation of his case before the Lord – Miles questions why Job would suddenly abandon his cause at the very end.

Miles contends that when freed from the presumption of the later Greek repentance gloss – the inherent ambiguity of the Hebrew suggests a very different translation of 42:1-6.

[You] know that you can do all things and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. [You say] who is this that hides counsel without knowledge? Therefore, I spoke more than I realized. [You say] Hear and I will speak, I will question you, and you declare to me. [Ahh], I had heard of you by hearsay (the words of my comforters) but now that my eyes have seen you I shudder with sorrow for mortal clay.

Miles suggests that this translation fits within the larger context of Job’s consistent refusal to back down in the face of God’s attempt to intimidate him. What seems to upset Job at this point is the realization that if God insists on deflecting questions of justice with displays of power– then all humanity is done for.

Job may have been reduced to silence but so has God been silenced by being brought face to face with the internal tension between his better and darker selves. The Lord now seeks to avoid facing his inner conflict by restoring Job’s fortunes. In the Lord’s time-honored behavior when he realizes he has gone too far – he makes double restitution without admitting culpability. Might we see in this a hidden expression of divine remorse?

Throughout the historical development of the Tanakh the Jewish scriptures struggle to reconcile the unfettered exercise of divine power with the constraint of divine justice. In other words, how can the split nature of the divine be understood – for the Lord God seems to have a dark as well as a light side to his identity, or in Job’s words the Lord gives, and the Lord takes away; yet blessed be the name of the Lord.

In the Psalms, we find the main divine assertion – I am the Lord whose power is made manifest through justice. Earlier in the Torah, we find Abraham repeatedly appealing to God’s better nature – invoking the attribute of justice as a necessary curb on God’s darker power-driven impulses. In effect, this is the argument Job now uses with God. Like Abraham, Job reminds God of the human expectations for God to live up to his assertion that divine power is made manifest through justice.

Accordingly, Jewish tradition understands that justice is imperfect – guaranteed by God but also at the mercy of his darker impulses. Time and again the Tanakh witnesses God’s justice winning over his power impulses. But as Job reveals this struggle is sometimes touch and go.

The encounter between God and Job has reduced both to silence. After the book of Job, the Lord God never speaks again in the Tanakh. In all the books that follow – God is either absent with the focus being on human interaction or heard through human repetition of God’s historical statements quoted from earlier passages in the Torah or the prophets. God makes a fleeting appearance in the book of Daniel but as the very remote and silent Ancient of Days.

The book of Job leaves a somewhat bitter aftertaste in the mouth. Yes, God restores Job’s fortunes and doubles his prosperity, and his better self eventually wins out over his darker impulses. But as Jack Miles notes – no amount of compensation can make up for Job’s loss of his previous family and servants – all merely the collateral damage flowing from the misjudged wager with the devil.

As for the Tanakh’s image of divine justice – well it’s mixed. In the books that follow Job, the simplistic fable morality – God rewards the good and punishes the bad – reasserts itself. We do find attempts to deal with unpredictability with the assertion that God will do neither good nor bad – somehow remaining detached and impartial. Only in the book of Job do we encounter a groping after a deeper and more paradoxical wisdom– that the lord will often do good but sometimes do bad. Justice is imperfect. From now on Job not only knows this about the Lord, but the Lord cannot escape knowing this about himself.