You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time?

Thursday of this past week, August 14th, was the commemoration of Jonathan Myrick Daniels, an Episcopal seminarian at Harvard’s Episcopal Theological School who in 1965 became the Episcopal Church’s most prominent civil rights martyr.

Robert Tobin (son of parishioners Bob and Maureen Tobin) in Privilege and Prophecy provides a narrative of the Episcopal Church’s evolving identity and social activism during the period 1945-1979. Drawing extensively on archival materials and periodicals from multiple sources, he provides an intimate picture of how Episcopal leaders understood their role and responsibilities during a time of upheaval in American religious and social life.

Tobin places Jonathan Daniels, a New Englander born in Keene, New Hampshire, against a background of Northern white Christian hypocrisy in the civil rights era. He calls out the white liberal romantic identification with Southern black suffering as an avoidance of the violence of racial discrimination on their own doorsteps.

So much Northern white Christian advocacy for racial equality was conducted from the safety and protection of positions of white privilege. John Butler, a prominent Episcopal churchman of the time, noted that demonstrating publicly in the South had required less personal courage than confronting the genteel racism of his Princeton parishioners.

Tobin comments on the iconic Rhode Island theologian, William Stringfellow, who perceptively noted that while Northern white liberals didn’t despise or hate Negroes, they also didn’t know that paternalism and condescension were forms of alienation as much as enmity.

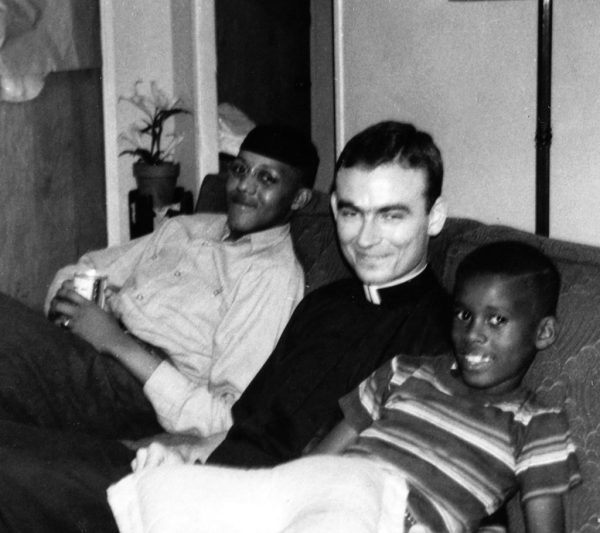

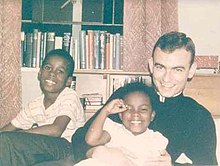

Jonathan Daniels – struggling with the paradoxes and ironies of his horror of racial oppression from his position of white privilege, like many other idealists of his ilk, joined the Selma Freedom Riders. But unlike many, he took to heart Stringfellow’s rebuke. He not only marched but also felt compelled to remain afterward to register black voters, tutor children, and help integrate the local Episcopal church.

Driven by a powerful spiritual awakening experienced during the reading of the Magnificat at Evensong , he explained:

I could not stand by in benevolent dispassion any longer without compromising everything I know and love and value …. as the price that a Yankee Christian had better be prepared to pay if he goes to Alabama.

In mid-August 1965, Daniels was shot dead as he shielded a young black activist, Ruby Sales, from the deadly aim of Tom Coleman, an unpaid special deputy, subsequently acquitted on the grounds of self-defense by an all-white jury.

John Coburn then Dean of ETS later confessed:

It took a long time to realize that Jon was a martyr. He was just a typical, questioning, struggling student, trying to make sense out of the issues, conflicts, and injustices of our society.

Yet with time, Daniels has come to be revered as a martyr in the Episcopal Church. As a man who embraced nonviolent protest in the face of the evil of racism – and who accepted the ultimacy of nonresistance because he had come to the realization that his possible death was the price that a Yankee Christian had better be prepared to pay if he goes to Alabama.

Jesus’ powerful accusation

You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time?

comes at the end of a difficult passage – seemingly flying in the face of our preferred image of Jesus as the peacemaker.

Although within the overall context of his ministry, Jesus preaches a message of peace, he recognizes that peace never comes without cost. Peace is never peace at any price – it must always be peace as the harbinger of justice. It’s not peace but justice that lies at the heart of Jesus’ concern. Luke 12 dispels any doubt we might still harbor concerning the real impact of Jesus’ recognition that conflict, which may even spur some to violence, is an unavoidable birth pang of the kingdom’s coming.

Jesus lived in a context riven by political and religious-sectarian violence. The question he addresses is whether violence can achieve justice.

We, too, live in a world increasingly riven by politicized violence. Domestically, what is the appropriate Christian response when incendiary rhetoric incites politicized violence among those who wish to wave a Bible in one hand and a gun in the other? Internationally, what is our humanitarian response in defense of nations and peoples subjected to colonialist violence – esp. when the disregard of a peoples’ right to exist trips over into genocide? While different options for action are open to us, all must proceed from an unwavering commitment to remaining clear-sighted in the face of the temptation to look away.

Whatever Jesus thought about violence, he was never one to look away. In his life and teaching, we detect a complex interleaving of two related strands of clear-sighted resistance – nonresistance and nonviolence as related and yet different forms of protest in response to systemic evil.

Nonresistance not only rejects acts of violence but also rejects confrontation when it has the potential to lead to violence. It’s essential that we grasp the point that nonresistance does not equate to nonaction. Nonresistance is the action of seeking solidarity with the victims by joining with them, even and especially when we ourselves become subjected to violence at the hands of the powerful. Practitioners on the path of nonresistance seek to change the world around them through sacrificial example.

By contrast, nonviolence seeks change through direct confrontation with the systems that maintain injustice and oppression through violence. The confrontation can be fierce, yet it stops short of resorting to violence to win the argument. When faced with the inevitability of violence, the path of nonviolence merges into the path of nonresistance.

In the larger frame, nonresistance and nonviolence are the two essential elements in Christian resistance. Jesus’ journey from life through death to new life is a demonstration of God taking the ultimate path of nonresistance. In his ministry, Jesus more often follows the path of nonviolence – calling out the systemic evils of injustice and oppression. But the new thing God does through Jesus is to bring about profound change through self-sacrifice on the path of nonresistance.

Returning to John Butler’s comment that confronting segregation in the deep South required less courage than confronting the smugly hidden racism of his Princeton parishioners alerts us to the dangers of hypocrisy when our Christian pretense to peace and love is but a fig leaf excusing us from facing up to the hidden and subtle forms of the violence that we claim to reject.

Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division!

We are living through another period when the level of division and conflict Jesus speaks about in Luke 12 permeates every level of our society. Although many of us are uncertain of how to respond to attacks upon the ethical values and principles that lie at the heart of our conception of democratic social and political order, the most important thing is to resist the temptation to look away – to avert our gaze from the appearances of the present time.

I could not stand by in benevolent dispassion any longer without compromising everything I know and love and value …. as the price that a Yankee Christian had better be prepared to pay if he goes to Alabama.

You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time?

Maybe it’s less costly to gaze upwards to interpret the patterns in the heavens than to look around and, with clear sight, confront the patterns of the present time?