All we have are the stories we construct to explain the world both to ourselves and to one another. The creation of narrative is the essential building block for discovering meaning and developing purpose. Any cursory Google or web search will reveal the considerable neuroscientific evidence in support of this assertion. For example – neuroscience researchers have repeatedly found that reader attitudes shift to become more congruent with the ideas expressed in a narrative after exposure to fiction (Green & Brock, 2000; Prentice, Gerrig, & Bailis, 1997; Strange & Leung, 1999; Wheeler, Green, & Brock, 1999).

The current profusion of online disinformation and conspiracy theories proves that there is always more than one way to tell a story, and the way you tell it influences beliefs and behaviors. Our awareness of competing stories increases the accuracy of our experience—to use a current slogan—there are facts, and then there are alternative facts. It’s vital to be able to distinguish between restrictive and toxic stories that restrict our capacity for creative responses and expansive stories that encourage creativity in our encounters with the world around us. We develop accuracy of perception, clarity of meaning, and purpose as we select between competing narrative storylines because it’s vital to know which storyline we are participating in.

The power of a storyline rests on its capacity to attract our attention and command our allegiance. We may construct a storyline to make sense of the world as we experience it, but once we do so, that storyline has the power to own us. The question of the current moment is, among competing storylines available to us, which storyline will we choose to believe? From among a bewildering choice of possibilities, which stories will command our allegiance?

With the spread of online information, the question of which stories we allow to shape our perceptions of reality is the question of the moment. We might be surprised to learn that this is not only a modern problem.

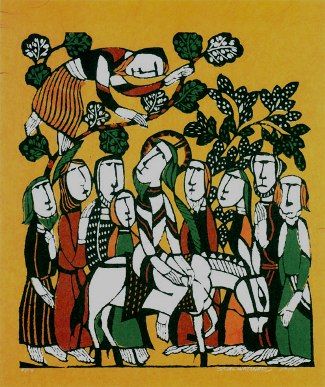

Palm Sunday offers a snapshot of competing storylines from Jesus’ last week in Jerusalem before the Passover and his crucifixion. On Palm Sunday, we witness a clash of competing storylines that are particular to Jesus’ 1st-century setting yet are also universal – timeless.

There is the storyline of sacred violence as the storyline of empire – that is – the unrestrained exercise of power to dominate and subjugate. From Rome to Rule Britannia, from the European legacy of colonial violence to the revival of Putin’s dream of the Russian imperium – not to forget to mention here the legacy and current ugly resurgence of American manifest destiny – the storyline of empire repeats endlessly across time.

Then there is the storyline of populist nationalism with its blood-socked dreams of liberation. On Palm Sunday the waving of palms was a significant echo from Jewish-nationalist collective memory. For some 160 years before, the triumphant Judas Maccabeus, the last leader of a successful Jewish revolt against foreign domination, led his victorious partisans into the Temple – which the Hellenist tyrant Antiochus Epiphanes had defiled by placing his statue in the Holy of Holies. Using palm branches, the Maccabean partisans cleansed and rededicated the sanctuary after its defilement. On entering the sanctuary, they discovered miraculously the last light of the Menorah still burning – an event Jews, today, celebrate in the festival of Hanukkah.

On Palm Sunday, this more recent Jewish storyline of national liberation found a powerful amplification in Israel’s more ancient founding story of liberation—commemorated in the festival of the Passover.

Inhabiting the amplified storyline of national liberation, the crowds ecstatically welcome Jesus into the city. They have yet to discover that they have chosen the wrong storyline. But they will do so – and rather quickly, with the result that they will pivot from exuberance to disillusionment and anger over the course of days. Jesus may be the Messiah, but his messiahship is part of a third storyline—that of the dream of God’s salvation, not of Jewish national liberation.

Casting our mind’s eye over the competing storylines converging on Palm Sunday, we observe that at the same time as Jesus was entering the city from the east, a second triumphal entry procession wound its way into the city from the west. The Roman Prefect, Pontius Pilate, at the head of a militia made up mostly of Samaritan mercenaries, had also come up to Jerusalem for the Passover.

As Prefect, Pilate was a vicious yet relatively low-level regional administrator who reported directly to Vitellius, governor of the Province of Syria. Each year at the Passover, Pilate came up to Jerusalem – forsaking the sea breezes of Caesarea Maritima— Herod the Great’s former capital and now the administrative center of the Roman occupation of Judea.

Pilate loathed and feared Jerusalem’s ancient rabbit warrens seething with civil and religious discontent. He most feared the pilgrim throngs crowding into the city for the Passover, swelling the city’s normal population of between 20-30,000 to over 150,000. The stability of Roman imperial rule required Pilate to come up to the city with a show of preemptive force to forestall any potential for insurrection.

Passover was Israel’s founding story of liberation from slavery. Pilate’s arrival was indeed a wise move, for the crowds hailing Jesus’ arrival were in insurrection mood. Being caught, as they would soon discover, in the wrong Messiah storyline—would have dire consequences for Jesus.

In the week leading to the celebration of Passover, we see with hindsight the lethal intersection of these three competing storylines – of imperial domination and political violence intersecting with populist resistance and longing for national liberation – both confronted by the next installment in the epic storyline of God’s love and vision for the world-through-Israel. This clash of storylines results in a chain of events that takes an unexpected turn – rapidly spiraling out of everyone’s control.

Emotionally and spiritually bloodied by our passage through the snapshots of Holy Week violence, we will eventually arrive at a different story – a new story – a bigger and better story – the unlikely story of Easter. Yet, on Palm Sunday, we’ve some way to travel before arriving there.

Holy Week is when we accompany Jesus on his journey to the cross. For some of us, this can be an intensely personal experience as our own experiences of loss and suffering – our passion – surface in identification with Jesus. For most of us, however, the nature of our Holy Week experience is less personal and more communal.

As liturgical Christians, we journey with Jesus as a community – each liturgical step along the way. Each snapshot is a prism refracting our own individual suffering and our identification with the overwhelming suffering of the wider world – an experience amplified by events in 2025.

Liturgy transports us together through sacred time. In sacred time, there is no past and no future, only the eternal now. Here, our individuality dissolves as we become participants in the events that engulf Jesus, erasing separation across time and then becoming now. As I’ve mentioned, we are no strangers to the storylines of sacred violence and national populist yearning for a messiah.

Choosing the right story to explain the world to ourselves is crucial. Choosing the wrong story leads only to disillusionment and rage.

Like the crowds praising Jesus as he entered the Holy City, we enthusiastically hail our next political savior until that is, – he or she no longer is.

We long to do the courageous thing – until that is, the moment when we don’t.

In sacred time, we become participants with Jesus—as if we were part of his band of disciples during this eventful last week. With them, we will share in the breaking of Jesus’ Passover bread and drink from his Passover cup. With them, we will accompany Jesus to the Garden of Gethsemane, where we, too, will fight sleep to keep watch with him through the night and early hours of Friday morning. With them, we will follow Jesus on the way of his suffering to the cross. For like them – we will long do the courageous thing – until the moment when we we won’t.

History does not exactly repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes.