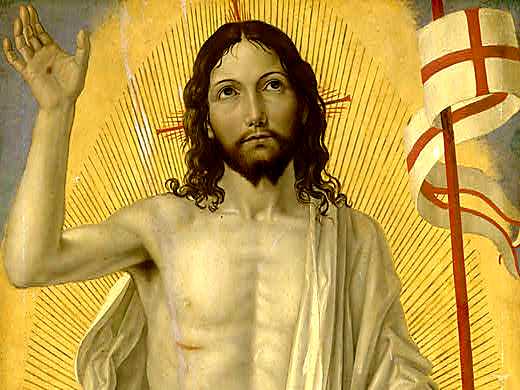

Image: Icon of the Resurrection by the Ukrainian icon writer Ivanka Demchuk. Unlike Western iconography of the resurrection, which portrays it as a Jesus-alone event, Orthodox iconography of the resurrection portrays Jesus raising Adam and Eve, symbolizing the general resurrection of the dead.

In her New York Times essay, The Prophetic, subtitled What American Literature’s Prophetic Voices Tell Us About Ourselves, the renowned writer Ayana Mathis in her first installment, titled Imprinted by Faith, recalls her childhood memories of growing up in a Black revivalist Christian tradition. She writes that:

the God of my revival childhood was all-powerful and relatively benevolent, but had a great many rules about what we should do (go to church 3x a week, live by the Word of God, literally interpreted) and what we shouldn’t do (listen to secular music, play cards, watch movies, drink). These commitments and privations would be rewarded with God’s love, palpable, like a bird alighting on a shoulder.

She describes leaving this world behind with the memorable image of plunging into the world on the other side of the stained-glass window. Mathis views the beginnings of her adult journey as one of growing beyond her conservative Christian origins to become an artist. Her journey was a learning how to disbelieve while still being imprinted by belief.

How to disbelieve while remaining imprinted by belief struck a deep chord in me. Mathis asserts that American literature –and by extension mainstream American culture – remains imprinted by belief, freighted by ideas about morality, justice, and standards for living. Her assertion is that whatever the condition of our belief at the personal level – as in do we, or don’t we? – the cultural impact of belief remains imprinted on us. That, despite many manifold wrongs and derelictions, the literary and cultural landscape of America remains deeply imprinted by the nation’s historically Christian heritage.

She notes that this Christian imprint has both good and not-so-beneficial consequences –in her phrase, it strikes a paradox. The Christian imprint on American society has often been used to perpetrate great evil. Christian Nationalism’s distortion of the Christian tradition is today still being used to justify racism’s doctrine of white supremacy, oppression of women and a multiplicity of other phobic responses to people of difference. Yet, at best, the Christian imprint continues to inspire decency and generosity, acting as a hedge against oversimplistic notions of society and the individual. Mathis’ assertion is that our Christian legacy asks us to truck in paradox, requiring us to wrangle with contradictory realities in mind and heart, discovering the sustenance and insight to be gained in the wrangling.

Bracketing her personal references to a revivalist upbringing, Mathis nevertheless speaks for many of us – I suspect- here in this church on this Easter morning. As good-aspiring, middle-class, over-educated, professionally successful, and predominantly white Episcopalians, few of us would pass the orthodox belief and devotional piety smell test. Yet here we are on Easter Day. Some among us may be a little surprised to find ourselves sitting in these pews. Yet, nevertheless, we’re here, despite being unable to give a full account for why we have been drawn here.

Perhaps we’re being drawn by memories of an earlier phase of family life as children or as parents of young children? Maybe it’s the influence of friends drawing us here? Perhaps – and this is the best reason of all – we’re drawn here by cultural tradition – tradition as the imprint of belief upon our personal struggle with disbelief? Deep down, being here reflects a questioning of certainties -once easily taken or rejected at face value, but alas no longer so. Many of us have lost confidence in the belief that Jesus being raised from the dead means all is right in our lives and our world.

We wrangle with disbelief while remaining mysteriously imprinted by belief as we reach for a fingerhold—to say a foothold here would be to overstate our confidence – on what it means to live well with a hope that, at times, aspires to the level of real courage – a tentative purchase on what it means to live well with a love demonstrated through generous concern for others. In short, we long for lives of generous toleration and concern for our neighbor while seeking to grasp after something ineffable.

If faith is an imprint we absorb from the shape of the culture around us, then belief is neither something we can possess nor something we can lose. It’s like ebb tide in the morning, only to return with evening’s flow. Belief is the expression not so much of objective faith in a collection of doctrinal propositions but a heartfelt experience of being deeply imprinted by a story capable of fostering meaning and purpose in our lives. A large and expansive narrative capable of adjusting our orientation to the world in all its evil as well as its glory. Faith is the practice of wrangling contradictory realities in mind and on heart and finding in the wrangling sustenance and insight for living well.

As an example of wrangling paradox, many today reject institutional Christianity for deeply Christian reasons. They reject the institutional Church for failing to live up to the expectations set out in Jesus’ teaching and the Christian culture it has spawned. Often citing the teachings of Jesus, secular humanism rightly judges the Church for its hypocrisy, its love of earthly power, and its manifold human abuses.

Wrangling with paradox is further illustrated in the debate between Tom Holland, a British historian of classical antiquity and author of Dominion: How the Crucifixion Shaped the Values of the Modern World, and AC Grayling, Master of the New College of Humanities in London and a well-known humanist philosopher.

The central contention between them relates to the origin of our contemporary definition of human dignity and personhood. AC Grayling, in his militant rejection of Christianity, contends that the values of modern humanism – ideas about human dignity, social justice and inclusive standards for living – emerge from the Enlightenment’s rejection of religion. There is a wonderful exchange where Holland challenges him, saying that the humanist values we cherish today are not simply remnants of pre-Christian classical antiquity, lying around neglected until rediscovered in the Enlightenment at the end of the 17th century. Our contemporary humanist values – aspiring to do good; valuing ethical action; protection of the individual especially the weak against the strong; the cherishing of vulnerability as a strength and not simply a weakness to be crushed by the powerful; the belief that might is not right – are all the direct product of the Christian revolution in the first centuries of the current era. Holland – with the historical evidence to support him – asserts our contemporary definition of what it means to be a human being flows directly from the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. He contends that modern humanist values are nowhere to be found in classical antiquity – a world where might was always right, where the weak were fair game for the strong, and where the only individuals with any rights were freeborn men – everyone else existing within various degrees of servitude and enslavement – in societies imprinted by not by faith but the crude transactional practice of calculated cruelty.

On Palm Sunday at the beginning of Holy Week while exploring the clash of competing storylines intersecting with dire consequences for Jesus’ during his last week in Jerusalem, I predicted that we would eventually arrive at a new and more expansive storyline – that of God’s dream for the renewal of creation. As Christian believers, we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus as the Christ, the longed-for promised one who came to change everything. But whether we pass the belief smell test or not, at the very least we celebrate a story that revolutionized the ancient world and ushered in a new and vastly more compassionate understanding of what it means to be human.

This morning, I’m not interested in forensically deconstructing the evidence for or against the resurrection to ascertain in an arid attempt to prove it did or did not happen. All human meaning and purpose are narrative in origin—in other words, we only ever have the stories we construct to make sense of our experience in the world. The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus is a story that fundamentally changed our understanding of what being human looks like.

The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus introduced a new storyline in the collective consciousness of the West and among all who have come to the Christian faith—a more expansive story that continues to imprint itself upon our cultural experience regardless of whether we believe in its literal truth or not. In this sense, secular humanism is not the antidote to Christianity but its natural heir.

Despite many manifold wrongs and derelictions, the literary and cultural landscape of America remains deeply imprinted by the nation’s historically Christian heritage. This heritage struggles with a view of humanity shaped by Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection – forcing us, in Mathis’ words, to truck in paradox – requiring us to wrangle with contradictory realities in mind and heart, discovering the sustenance and insight to be gained in the wrangling.

The imprint of Christian faith shapes a cultural landscape where human dignity and Christian love, expressed as justice, are enshrined in the protections of the rule of law. The imprint of Christian faith, whether as cultural legacy or principled belief, empowers us to call out and resist the cyclic embrace of calculated cruelty as a transactional means to political ends – whether as remembered history or experienced within the flow of present-time current events.

But on Easter Day in 2025, you might want to ask, what about Jesus’s bodily resurrection? Well, there you have it—a curious paradox: Jesus died on the cross, but Christ was born in an empty tomb. To disbelieve while being imprinted by belief is the best description I can find for living with the paradox at the heart of our cultural landscape. Wrangling to disbelieve while still imprinted by faith, we should be careful not to rule anything out.