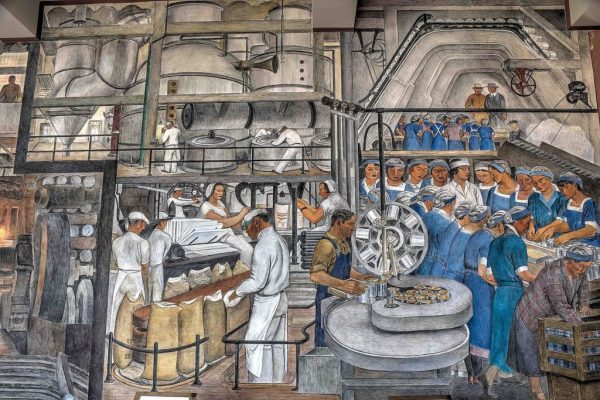

Picture taken from the murals in Coit Tower, SF depicting the idealism of the New Deal.

I look forward to Labor Day weekend. Who does not enjoy a 3-day break? However, because my day off is Monday, 3-day weekends are somewhat compromised for me. Yet, I rejoice in them because I know that many people I live and work with will enjoy three consecutive days of relaxation as summer ebbs into autumn.

The UK enjoys six 3-day or bank holiday weekends, two additional public holidays – Good Friday being one, and an average of 3 – 4 weeks of paid vacation leave a year. The average vacation leave in the US is 11 days a year. There’s an intuitive connection here to be fleshed out as it were – between American attitudes to paid leave, low pay, long hours, falling productivity, and a plethora of societal ills. These include increasing family and marital breakdown, rising tides of depression, suicide, and addiction, and rising civic strife. The American attitude towards work and recreation – indelibly shaped by the protestant work ethic and the immigrant experience is today something of a problem – with an adverse impact on the nation’s sense of well-being. Thus, current polls show that people remain pessimistic about their economic well-being despite record job creation, falling inflation, good economic growth prospects, and a booming stock market.

The Labor Day weekend is an important national observance. It is not only a well-needed three-day respite as summer ebbs into fall, but also a spotlight on current attitudes and practices that undermine American societal well-being.

How many of us know Labor Day’s origins? The US Department of Labor website tells us:

Labor Day, the first Monday in September, is a creation of the labor movement and is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers. It constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country.

A yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country. Really?

In 1993 on the 100th anniversary of organized labor in Rhode Island, Rhode Islanders were reminded of the establishment of the first Monday in September as a legal holiday. A direct result of the 1893 financial panic – following a previous decade of worker agitation the General Assembly, under the prodding of elected representatives from various mill towns, finally joined the bandwagon, and Governor D. Russell Brown signed the authorization.

Arriving in RI was a novel experience for me. Here I found the vestiges of an old Labor movement culture where certain unionized workers such as firemen, police, state employees, and teachers enjoyed privileged work protections and secure pensions that contrasted with the denial of these very privileges to the rest of the working population. Following its decline as an industrial powerhouse, Rhode Island’s failure to transform itself into a dynamic opportunities economy only fuels resentment as the tax burden to support the generous work privileges for the few falls on the many denied similar benefits. The economic plight of RI is bedeviled by an inward-looking parochialism summed up by the much-used phrase – I know a man. The Washington Bridge debacle demonstrates the consequences when the man you know is incompetent and seemingly unaccountable – not an unfamiliar story in this state.

Rerum Novarum (from its first two words, Latin for “of revolutionary change”, or Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor, is the encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It was an open letter, requiring the hierarchy to address the condition of the working classes.

Rerum Novarum discussed the relationships and mutual duties between labor and capital, as well as government and citizenry. Of primary concern was the amelioration of The misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class. It supported the rights of labor to form unions, rejected socialism and unrestricted capitalism while affirming the right to private property.

John Paul II on its 100th anniversary reaffirmed Rerum Novarum in Centesimus Annus which affirmed work as our individual commitment to something greater than our own self-interests – namely the greater good. If one flourishes at the expense of another’s languishing – then society fails.

The Law of Moses and the teaching of Jesus recognized that labor is the basis for all human flourishing because labor not only generates wealth but also bestows dignity on the human person. Today, we recognize three core psychological needs necessary for human flourishing: someone to love and be loved by, a safe place to live, and an activity that bestows dignity fostering a sense of meaning and purpose.

Furthermore, in the sabbath regulations, both the Law and Jesus recognized the necessity for a healthy work-life balance. The balanced relationship between work and leisure contributes to individual as well as societal well-being.

The US Conference of Catholic Bishops -the most politically conservative episcopal conference in the world, nevertheless cites 13 Biblical references in support of their affirmation that:

The economy must serve people, not the other way around. Work is more than a way to make a living; it is a form of continuing participation in God’s creation. If the dignity of work is to be protected, then the basic rights of workers must be respected–the right to productive work, to decent and fair wages, to the organization and joining of unions, to private property, and to economic initiative.

Marx defined capital as stored labor. The mere mention of Marx is enough to induce apoplexy in hard-right politicians and their supporters. It’s one of those curious paradoxes that those on the hard right – J.D Vance being the most current example – are flocking to the Catholic Church while holding economic views in sharp conflict with the social teaching of that Church. As over 100 years of Catholic social teaching asserts – to champion the rights of workers, to assert the dignity of labor, and to confront the abuses of labor at the hands of unrestrained capitalism is not Marxism – it’s Christianity!

The accumulation of obscene wealth by the few at the expense of the many whose labor generated it has clear ethical limits rooted in our deeper religious traditions of a just society. As we celebrate Labor Day on the first Monday in September 2024, we might do well to remember the mantra from the HBO series Game of Thrones – paraphrased as November’s coming!