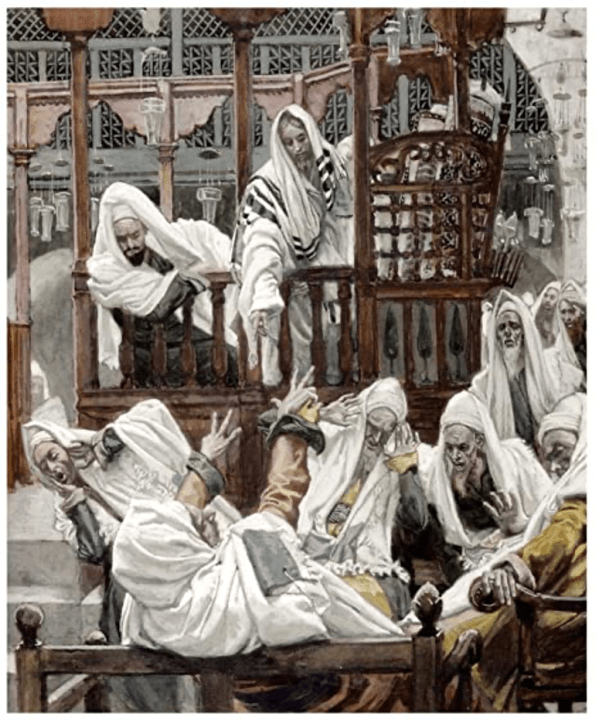

Image courtesy of Redeeminggod.com

Today is the launch of our public stewardship renewal campaign for 2026. It will run until November 9th. Letters with educative documentation, along with an estimate of giving card, allowing for the vagaries of the US postal service, should land in your mailboxes by the end of this coming week or hopefully sooner. Now, no one wants to hear – even on the Stewardship launch Sunday, a sermon distorted into a harangue for more money. So you can rest easy, I’m not interested in doing that either.

I want you to picture the scene Luke depicts in today’s gospel.

Ten men stand at a distance. Ten voices cry out—not for justice, not even for understanding, but simply: Jesus, Master, have mercy on us. And Jesus—without touch, without spectacle—says, Go, show yourselves to the priests. They go. Ten are cleansed. But only one turns back.

And Luke pauses here to let us feel the implication of the story – one not lost on Jesus’ immediate 1st-century audience. Because the one who returns is a hated foreigner, a Samaritan who falls at Jesus’ feet, giving thanks. His gratitude becomes an act of recognition, an awakening of something within him, as he becomes overwhelmed by hope. For gratitude is never just backward-looking; it is the soil in which the future grows.

Five centuries before this moment, the prophet Jeremiah wrote to another group of people living outside the fold of inclusion—a people rendered strangers in a foreign land -Israel’s exiles in Babylon. They were displaced, disheartened, and desperate to go home to rebuild what had been lost. So Jeremiah’s letter would have shocked them. He didn’t say, Hold on, you’ll be back next year. He said: Build houses and live in them. Plant gardens and eat their produce. Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you. (Jer. 29:5–7)

In other words: Hope is not waiting for escape—it is beginning again where you are. Jeremiah’s hope was not naïve optimism. It was a fierce, grounded trust that God is still at work, even in exile. Like gratitude, hope starts by paying attention to what is already possible. For gratitude is never just backward-looking; it is the soil in which the future grows.

The healed Samaritan and Jeremiah’s exiles are kin in spirit. Both live outside the center of inclusion. Both find hope in despair. Both embody what we might call resilient gratitude—the capacity to thank God even before everything is fixed.

The Samaritan’s turning back is his equivalent to planting a garden in exile. He does not rush back into a normal life, the life he must have longed to return to during his years of being shunned. He turns toward the source of his gratitude. And in that turning, he is not only cured but discovers a new kind of wholeness.

Jesus’ final words to him—Your faith has made you well—echo Jeremiah’s promise: For surely I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for your welfare and not for harm, to give you a future with hope.

Stewardship is about the fostering of our sense of gratitude for what God has already given. From gratitude, hope emerges, trusting that the same God will bring future abundance to life.

Stewardship, then, is nothing less than the practice of hope in action. It requires attentive care. St Benedict loved to tell his monks that stewardship is the exercise of tender competence in ordinary things. Jeremiah said, Build houses… plant gardens… seek the welfare of the city. Stewardship does precisely that—it tends, builds, and plants for the future even when the present feels uncertain.

Every pledge of financial generosity, every act of service, every hour given in ministry is an act of trust that God’s future – already coming to fruition through us is worth investing in. It says, With our time and our treasure, we believe our story isn’t over.

In the Samaritan’s turning back, we glimpse the same truth: gratitude is never passive. It propels us forward into participation—into giving, healing, reconciling, and most importantly investing in the future in a community where our commitment to one another becomes more important than our prized self-sufficient individuality. The key to recognizing gratitude is to never resist for too long, an opportunity to express generosity towards another.

To give thanks in the midst of uncertainty is to refuse to be ruled by fear. To give generously, even when anxious about the future, is to declare that God’s promise of abundance is greater than our fear of scarcity.

When we live this way, we become what Jeremiah envisioned—a community that plants gardens in exile, a people who embody hope through gratitude expressed in generous living. People who make possible a future we cannot yet see.

As I often remind us, it’s only together that we can achieve so much more than any one of us alone. As we enter our own season of stewardship, the fostering in us of our tender competence and love for one another in community, we need to remind ourselves that it is to God we must continually give thanks for the enjoyment of our abundance amidst the experience of change, challenge, and uncertainty.

Like Jeremiah’s exiles, we are called not to wait for the perfect moment— but to build now, plant now, give now, hope now. You and I may not be here tomorrow, yet through what we tend today, the community we build will remain.

Every pledge, every gift, every offering of time and skill says that we believe that God still has plans for us. We believe that love will have the last word. That is when we turn back, as the healed Samaritan did—when we give thanks and offer ourselves anew—we open the way for God to create a new future together. Gratitude is not the end of faith. It is the beginning of renewal. Jeremiah calls us to build despite our present experience of alienation and exile from an America we still cherish in our hearts.

Gratitude is the seed of hope, and hope is the architecture of the future God is already building through us.

Ten men stand at a distance. Ten voices cry out—not for justice, not even for understanding, but simply: Jesus, Master, have mercy on us. And Jesus—without touch, without spectacle—says, Go, show yourselves to the priests. Ten go but only one turns back in gratitude. Nine are cleansed, but only one is made whole. And just to rub it in for his xenophobic Jewish audience harboring an aversion and hostility towards Samaritans, Jesus asks: Were not ten made clean? Was none of them found to return and give thanks to God except this foreigner?

For gratitude is never just backward-looking; it is the soil in which the future grows.